Saint Seraphim of Sarov

[1]

Introduction

St. Seraphim was born to Isidore Ivanovitch and Agathia

Photievna Moshnin on the night of 19-20 July[2]

1759[3]

in Kursk (Курск), Russia.[4]

The name given to him at baptism was Prokhor (Prochoros), after the disciple of

the seventy and companion and co-worker of St. John the Evangelist (28 July and

04 January; cf. Acts 6:1-6). St. Seraphim was raised devoutly by his mother,

his father having died in 1760. Like many saints, various signs in his life as

a child pointed out that he was destined to bring glory to our Lord’s Name in

some special way. At the age of nineteen he joined the Sarov Monastery, and

over the next sixteen years lived a communal life, serving in various

obediences as he grew as a novice to the time of his tonsure, and then to the

ordained as deacon and finally priest. Beginning in 1794 St. Seraphim departed

the community to live for 31 years as a hermit and solitary, undertaking

various ascetic tasks that further prepared him for a ministry to others, when

he would become a brilliant light set on a hill that no one could cover. In

1825 St. Seraphim came out of seclusion and began serving as a true staretz (an elder or spiritual father who functions as venerated adviser and teacher) who

was blessed by God’s Grace with powers such as healing, knowledge, and

foresight, serving those who came to him in great numbers from all walks of

life, as well as his fellow monastics—especially the sisters of the

Diveyevo Convent. On the second of January, 1833, St. Seraphim died at the age of 73 while

kneeling in prayer after serving as a staretz for just over seven years,

although his ministry as a saint certainly continued. On 19 July 1903, the

Church canonized St. Seraphim; in attendance were Tsar Nicholas II, Tsaritsa

Alexandra, the grand dukes, many bishops, and thousands of the faithful who had

flocked to Sarov for the occasion from all across Russia. Saint Seraphim remains

one of the best-loved saints of the Russian Orthodox faithful. At the time of

this writing, the saint’s relics are preserved in the Diveyevo Convent.

Historical Setting

A number of actions taken by Peter “the Great” (reigned

1682-1725) and Catherine II (reigned 1762-1796) changed the face of Orthodoxy

in Russia, and so have some bearing on understanding events in the life of St.

Seraphim.

In the centuries from the

conversion of the Rusę up through the 17th century, the relationship

between the Church and the State followed after the Byzantine role model: a

diarchy represented by the sacerdotium

and imperium. But Peter had no

intent to share his power, nor allow anyone to be in a position to question his

rule. After he took over the conduct of state affairs he began his efforts at Westernizing

Russia.[5]

The patriarch Hadrian openly tried to sabotage the reforms. Peter worked to

neutralize his influence by appointing bishops from Ukraine who were much more

predisposed toward Western habits. When Hadrian died in 1700, Peter seized the

opportunity to remove this thorn from his side. Initially he simply refused to

allow a new patriarch to be elected, and instead appointed a locum

tenens that was sympathetic to his cause.

When he determined that the State could successfully operate without a

patriarch, the office was abolished and replaced by a Synod (a condition that

lasted until 1917) that was nothing more that an organ of the government whose

members were nominated and deposed by the tsar, and who took an oath of

allegiance and obedience to him—i.e., the church “legally” became

subservient to the State.[6]

Peter’s attitude toward the sacerdotium was clearly captured in the regulation

that brought about this change: “The fatherland need not fear from the

synodical administration the same mutiny and disorder as occur under a single

ecclesiastical ruler. For the common people, not knowing the difference between

the spiritual and autocratic power, and being impressed by the greatness and

fame of the supreme pastor, think him a second sovereign, possessing a power

equal or even above that of the autocrat, and believe the church to be another

and higher state. And if the people continue to think this, then what will

occur when the sermons of the ambitious clergymen add fuel to the flame? Those

of simple heart will be so perverted by this idea that they will respect the

supreme pastor more than the autocrat, and if there is discord between the two,

more sympathy will be shown the spiritual ruler than the secular. They will

venture to fight or mutiny for his sake, and deceive themselves into believing

that they are fighting for God Himself and that their hands are not stained but

blessed by the blood that they may shed. Such popular beliefs are of profit to

those who are hostile to the sovereign, and they incite the people to

unlawfulness under the guise of religious fervor. And what if the pastor

himself through self-pride grasped the opportunity?”[7]

Peter was not just happy, however, with subjugating the Church hierarchy, he

wanted to utterly demean it. To this end he established “The Vastly

Extravagant, Supremely Absurd, Omni-Intoxicated Synod” that publicly performed

gross parodies and debaucheries throughout his reign.[8]

Beyond attacks on the hierarchy,

Peter sought to place restrictions on and control the “white” (non-monastic)

clergy. The building of new churches was restricted. Church finances were

controlled to the point that the clergy could not spend even small sums without

the permission of the State. By an edict of 1702, they were required to report

births and deaths weekly.[9]

In 1708, “a secret ukase of the tsar enjoined the clergy to violate the secrecy

of the confession, ‘to diligently question their spiritual children, people of

all ranks, during confession, whether they were going to rebel or had evil

intentions or conspired with any one to rebel or to do harm to the State, or

made plans with anyone to commit brigandage or murder’. If any such ‘evil intention’

was discovered, and it was established that there were plans to ‘put it later

into effect’, the clergy were obliged to report [it] immediately…” thus making

them government informers.[10]

In 1722 they were required to take an oath of allegiance to the emperor,[11]

after which they were obligated to play the role of informant.

The “black” clergy were not immune

from Peter’s attention. In fact, he thought of them as “the origin of

innumerable disorders and disturbances.”[12]

He sought not only to control the source of the Church’s leaders, but to reduce

and even eliminate the influence it had with the people through its extensive

social work. New monasteries were not to be founded without special permission.

Monks were forbidden to live as hermits (it was not until “1822, just over one

hundred years after it had been imposed, [that] the ban on sketes was lifted…”[13]).

Laymen (e.g., sextons, readers, choristers, scribes) were ejected from residing

in the monasteries, and were only allowed to enter during times of the divine

service. Monastics were bound to one monastery, and not allowed to change to

others except under exceptional conditions, and then only with written

authorization. Nuns were forbidden to go out without written permission, and

then only for short periods of time. Novices were not to be received under the

age of forty, nor without the permission of the Tsar. Monks and nuns were not

allowed to have paper and ink in their rooms, being able to write only with

permission and in a special corner of the refectory (common hall).[14]

Catherine II went even further in 1763. She closed down something like 568

monasteries out of the 953 in existence at the time (the actual numbers

reported vary slightly, depending on the source), and greatly reduced the

membership of the ones left open. Her decrees also, not unlike Peter’s, forbid

the profession of new monks and nuns without the express permission of the

central government.

While Peter took steps to destroy

any threat to his rule the Church might have represented through its clergy, at

the same time he also sought to use its resources as an instrument in his

cause. This began at the end of the 17th century by drawing on its

financial wealth through non-repayable loans and grants. By the early 18th

century, all of the Church estates were factually secularized; so two-thirds,

and subsequently as much as seven-eights, of the church revenue was confiscated

and given over to the state.[15]

In the first years after the Church “reform” the government was receiving some

100,000 roubles a year in revenue from church possessions (not counting sums

received from the outright seizure and sale of certain lands, extraordinary

confiscations of church funds and treasuries, or “gifts” it received from some

of the larger monasteries and convents). Catherine II completed this process in

1764 by formally secularizing all church estates.[16]

In spite of all this oppression by

the State against the Church, or rather perhaps because of the “purifying fire”

that such actions produce, Russia experienced a spiritual renewal in the 17th-18th

centuries—a renewal that, in hindsight, can be viewed as a preparation of

the faithful for the terrible persecutions that would soon be brought upon the

land by an antichrist: the Soviet. One measure of the revival that took place

is that the lifting of restrictions against the Church under the Tsars of the

18th century was followed by a rapid growth of the Church; e.g., by

1914 there were 11,845 professed monks and 9,485 novices, and 17,283 professed

nuns and 56,016 novices, and over 300 new monasteries had been founded. But

perhaps more telling spiritually is the list of venerable monks, nuns, and

other saints that appeared during this age. Consider the following sampling: St. Tikhon of Zadonsk (1724-1783); Venerable Father

Paisius Velichkovsky (1722-1794); Bishop Ignatius Brianchaninov (1807-1867);

Bishop Theophan the Recluse (1815-1894); the fathers of Optina, including

Leonid (1769-1841), Macarius (1783-1860), and Ambrose (1812-1891); the fathers

and mystics of Valaam; and the solitaries of the Roslavl forests.[17]

Of course to this list we must add St. Seraphim, the subject of this essay.

Childhood

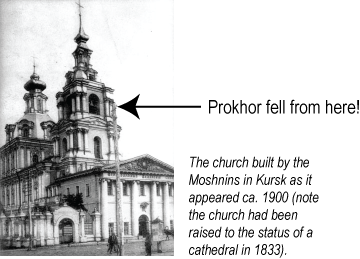

St. Seraphim (Prokhor) was the third child[18]

of a respected and wealthy, but pious, merchant family. One visible expression

of this family’s piety is found in the fact that St. Seraphim’s father,

Isidore, a stonemason and bricklayer, in 1752 had taken up the task of building

a two-altar church in Kursk (one altar was dedicated to St. Sergius of Radonezh

and the other to Our Lady of Kazan), following the design traditions of the

famous architect Rastrelli. However, Isidore died at the age of 43 in 1760

before its completion. Saint Seraphim’s mother—unwilling to give up or

trust the building to others—took up the task herself, even to the point

of supervising the daily construction activities for the twelve-year period

that was needed to finish the work. To provide for her family, Agathia also

took charge of the family’s brick factory until Alexei, St. Seraphim’s older

brother, was old enough to take over its management. Agathia was respected by

her neighbors for her goodness and for her loving care of the sick, orphans,

and widows; this love for neighbor was inherited by St. Seraphim as he later

revealed when besieged by crowds on all sides. Another expression of Agathia’s

piety was shown when she did not interfere with his stated desire to become a

monk, but rather blessed him with a large copper cross that he wore openly on

his chest even unto death.

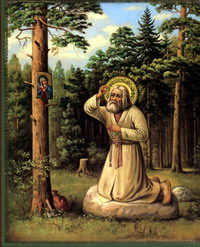

God’s Grace was actively at work in

St. Seraphim as a child, as illustrated by the following two incidents:

Like any child, St. Seraphim often

followed his mother around, and so one day at the age of seven, when Agathia’s

church construction oversight activities took her to the top floor of the bell

tower, he naturally went along. However, while she was busy instructing the

workmen, St. Seraphim’s curiosity enticed him too close to the edge of the

platform, and he fell to the ground. Agathia, rushing down the stairs to the

ground, had her dread turned into astonishment when she found her son standing

on his feet, whole and unharmed. A Fool-for-Christ living in Kursk witnessed

the incident and remarked that the child must surely be one of God’s elect.[19]

|

|

|

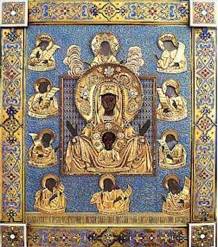

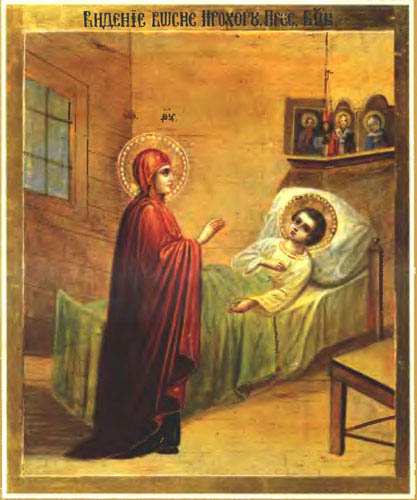

On another occasion at the age of ten, St. Seraphim had become

very ill. The Mother of God, in what was her first—at least visible—visitation to St.

Seraphim, promised to heal him.

Her promise was soon fulfilled in the following way. A church

procession was winding its way through Kursk. In the procession the

wonder-working Kursk Korenaya (Root) Znamenie (Sign) icon (8 Sep and 27 Nov) was being carried.

When it began to rain heavily, the procession detoured into the yard of St.

Seraphim’s home (either to find shelter for the Icon or to make the way

shorter). Agathia carried St. Seraphim out to meet the Icon and placed him

under the care of the Mother of God; he recovered that same day.

|

|

|

As St. Seraphim grew into a young

man, his mother and his brother Alexei decided that he should start working in

the family mercantile store. Not happy with having to deal with material

concerns, St. Seraphim sought to discern spiritual truths in the day-to-day

events in the life of a tradesman, an approach found in the works of Bishop

Tikhon of Zadonsk (Spiritual Treasures Garnered in the World)—a contemporary of the saint. Like others of

his age, St. Seraphim would spend his free time with friends. However, unlike

most young adults but like many of the Saints, rather than play games and look

for other amusements, they would read the Holy Scriptures and Church Fathers

together.

Seeking a Vocation

The occasion for St. Seraphim receiving a cross at the hand

of his mother, as mentioned above, was her blessing for him to pursue life as a

monastic.

|

|

However, rather than make such a decision on his own, he—as well five likeminded friends—decided to make a pilgrimage to Kiev (Kyiv), a 450-km journey one-way on foot. Kiev was the cradle of Christianity for the Rusę and home of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra (Kiev Caves Monastery), considered to be the mother house of all Russian monasteries. Furthermore, at the Lavra were to be found the relics of those considered to be the founders of monasticism in Russia: St. Anthony (10 Jul, 28 Sep, and 2nd Sunday of the Great Fast) and St. Theodosius (03 May, 28 Aug, and 2nd Sunday of the Great Fast). (The Saints of the Nearer Caves, or Caves of St. Anthony, are honoured on September 28, the Saints of the Far Caves, or Caves of St. Theodosius, on August 28, and they have a common Feast on the Second Sunday of the Great Fast.)

After worshiping at the Holy Places

and venerating the Holy Relics, the young men all sought guidance for their

life from a startez (spiritual director). They were told they should visit the Elder

Dositheus[20] at the

nearby Kitaev Monastery. On seeing St. Seraphim, the Elder peremptorily blessed

him to go to the Sarov monastery[21]

and gave him this testament:

“Go, child of God, and stay there.

That place will be to thee for salvation, with the Lord’s help. There thou

shalt finish thy earthly pilgrimage. Only try to acquire the unceasing

remembrance of God through the constant invocation of the Name of God thus:

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner! Let all thy attention

and training be in this: walking and sitting, working and standing in Church,

everywhere in every place, coming in and going out let this constant cry be on

thy lips and in thy heart; with it thou shalt find rest, thou shalt obtain

spiritual and bodily purity and the Holy Spirit Who is the source of all

blessings will dwell in thee and will direct thy life in holiness, in all piety

and purity. In Sarov the Superior Pachomius is of God-pleasing life; he is a

follower of our Antony and Theodosius.”[22]

In this way the question of

monasticism and monastery was decided forever for St. Seraphim. Four of the

friends that accompanied St. Seraphim eventually took up the monastic life as

he did (two of them accompanied him to Sarov while the other two chose—or

were assigned to—other monasteries). On returning to Kursk, he took the

next two years to settle his affairs,[23]

yielded up his share of his inheritance in favor of his brother, and set out on

the 560-km trek to Sarov.

Novitiate

Saint Seraphim and his two companions arrived in Sarov[24] on the eve of the Feast of the Entrance of the Most Holy Theotokos into the

Temple, 20 November 1778. The entrance into the monastery—the gates of

the bell tower—were open and the young men were able to proceed to the

Dormition Church and take part in the vigil service. It seems somehow

appropriate that St. Seraphim began his new life in the “temple” by celebrating

the time the Mother of our Lord began her time in the Temple.

The next day the abbot, Father

Pachomius, officially received the three young men into the monastery. In

Prokhor (St. Seraphim) the abbot recognized the soul of a great future ascetic,

and so, for spiritual direction, he committed him to the experienced elder,

Father Joseph, the monastery bursar. Saint Seraphim’s first obedience was as cell

attendant to Father Joseph. In accordance with the general rule (the 4th

c. rule of St. Pachomius), St. Seraphim was given various additional

obediences. He served in the bakery preparing bread and prosphora. He worked in

the furniture shop where he was so proficient that he earned the nickname of

“Prokhor the carpenter.” He performed the task of waking the monks, was church

sacristan, sang on the cliros, and participated in the general obediences of

cutting wood, maintaining the grounds, and such. His solitary devotions and

reading occupied him late at night, allowing himself only four hours of sleep a

day. He not only read, as expected, the Holy Scriptures, standing before the

icons, but he tried to wholly assimilate and practice their meaning. In

addition, he read widely of the Holy Fathers and the Menologion of St. Dmitri of

Rostov. Through it all St. Seraphim distinguished himself by his unmurmuring

obedience, carrying out all of his assignments as best he could both in mind

and might. His devotion, however, did not dampen his youthful cheerfulness,

which made him popular with his fellow novices.

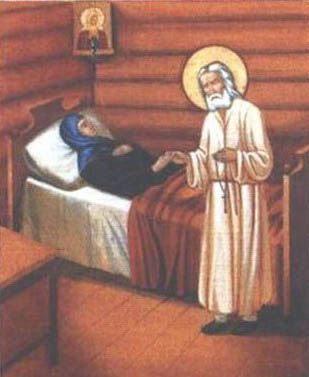

During his second year in the monastery, in 1780, St. Seraphim became ill from

dropsy. His condition continued to deteriorate over the next three years to the

point that he could no longer leave his bed, and the abbot was ready to call

for a doctor. St. Seraphim requested instead that heavenly medicine—the

Eucharist. After that St. Seraphim was quickly restored to health. Later St.

Seraphim related that after the Eucharist had been served, that the Theotokos

appeared to him surrounded by light indescribable, accompanied by the Apostles

Peter and John the Theologian, to whom she turned and said, pointing to

Prokhor, “He is one of our family.” The Mother of God then touched St. Seraphim

on the thigh with her scepter from which water came forth. Until the end of his

life a deep impression remained on his body there.

After he had fully recovered his strength, St. Seraphim sought and received permission from the abbot to leave the monastery in search of contributions to build an infirmary and chapel in thanksgiving of his healing. His travels carried him as far as Kursk, where it is reported that saw his earthly mother again. In 1784, the foundations of the Church of Saints Zosima and Savvas (Zossima and Sabbatius of Solovetz; 17 Apr) were laid, and St. Seraphim himself made the Cyprus-wood altar.

St. Seraphim’s own view of his novitiate is perhaps found in the advice he gave

in later years to young monastics, as captured in the following quotes.

“Whatever the way by which you came into this monastery, do not be discouraged:

God is here. Monastic life is not easy. Do not consider giving up one monastery

for another at your first disappointment. A novice must will to persevere. From

the hour he enters the monastery to the day of his death the life of a monk is

but a terrible struggle against the world, the flesh, and the devil.”

[25]

“Obedience is the foremost virtue, before fasting and praying.” “If you have

handiwork, work on it alone. If you are in your cell without any handiwork,

engage in some reading, in particular the Psalter.” “Those who have truly

decided to serve the Lord God should exercise themselves in remembrance of God

and the ceaseless prayer to Jesus Christ. In handicrafts, or anywhere on

obedience, ceaselessly repeat the prayer, ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me,

a sinner.’ Be heedful in prayer, that is, collect your mind and unite it with

your soul. At first one day, then two, increasing, then saying the prayer with

the mind alone, attentive to every separate word. When God warms your heart

into one spirit, the prayer will flow in you without end, and will always be

with you, delighting and nourishing you. … When this spiritual food is

constantly within you—that is, discourse with the Lord Himself—then

why go visiting the brothers’ cells, even should they invite you? Truly, I tell

you that idle talk is love of idleness.” During fasts “take food once a day,

and an angel of God will cling to you.” “Acquire peace and thousands around you

shall be saved. If it is impossible not to become disturbed, then at least try

to hold your tongue, according to the Psalmist, ‘I was troubled and spake not.’

In order to escape judgment, you should be attentive to yourself and ask ‘where

am I?’” “You should throw off despondency, and strive to have a joyful spirit,

not a sorrowful one, in the word of Sirach, ‘Sorrow destroys much, and there is

no use for it.’ This sickness is healed by prayer, restraint from idle talk,

handiwork as you are able, reading the Word of God and patience; because

despondency arises from illness.”

[26]

“We have no reason to be sad, for Christ has conquered all. He has bestowed

life upon Adam, freed Eve, and killed death.”

[27]

Tonsure

Eight years after his arrival at the monastery, 13 August 1786, the

twenty-seven year old Prokhor was tonsured by Fathers Joseph and Isaiah. Abbot

Pachomius, impressed with the young man’s ardent, “seraphic” (flaming) faith,

gave him the name of Seraphim. After having been received into the ranks equal

to that of the angels, St. Seraphim increased his podvig—ascetic

struggles—with a focus on silence. “More than anything else one should

adorn oneself with silence; for St. Ambrose of Milan says: I have seen many

being saved by silence, but not one by talkativeness. And again one of the

Fathers says that silence is the mystery of the future age, while words are the

implement of this world (St. Isaac the Syrian). Only sit in your cell in

heedfulness and silence, and by every means strive to draw near to the Lord,

and the Lord is ready to transform you from a man into an angel, and to whom, He says, will I look, but to him that is

meek and silent, and that trembleth at My words? (Is. 66:2). When we remain in silence, our enemy the devil will have

no success with regard to a man with a hidden heart; by this, however, must be

understood silence in the mind.”[28]

Diaconate

On 27 October 1786,[30]

St. Seraphim was ordained to the Diaconate by Bishop Victor of Vladimir. While

the mere fact of St. Seraphim’s promotion was evidence of the esteem with which

he was held by Abbot Pachomius, his regular service at the altar was perhaps

more so. Saint Seraphim had this to say: “Our Fathers of blessed memory, the

Abbot Pachomius and the treasurer Isaiah, both saintly men, loved me as their

own souls. And they hid nothing from me; and they cared for the things which

were profitable for their souls and for myself. [And] when Pachomius served

[both in and without the monastery], he rarely did so without me, poor

Seraphim.”[31] In

preparation for service, St. Seraphim would spend whole nights in prayer; after

the service, he would faithfully remain behind, meticulously caring for the

vessels, vestments, and general order of the sanctuary. The importance of these

duties were expressed by St. Seraphim in various ways. “Even the dust of the

Temple of God is sacred. There is no higher obedience than a Church obedience!

And were it only to wipe the floor of the house of the Lord with a cloth, this

will be counted higher than any other action by God! And all that is done

there, and how you go in and out, all ought to be performed with fear and

trembling and with unceasing prayer.”[32]

Saint Seraphim’s faithfulness in such matters are, perhaps, best expressed by the

graces he received during this period: he was privileged to see angels

ministering at the altar and heard their singing. He said “nothing can be

compared to this heavenly music. In my bliss which nothing could disturb I

would forget everything. I wasn’t conscious of being on earth; I only

remembered coming into church and leaving it… but the time spent at the altar

of the Lord was wholly light and splendor. My heart melted like wax in the heat

of that ineffable joy. One Holy Thursday, I celebrated with Father Pachomius.

Before the ‘Entrance’ with the Gospel, while the priest in the sanctuary was

uttering the words: ‘Grant that the holy angels may enter with our entrance to

minister with us and to glorify thy goodness,’ and while I was standing before

the Royal Doors, I was suddenly dazzled as though by a sunbeam and, as I

glanced towards that Light, I saw our Lord Jesus Christ in his aspect of Son of

man, appearing in dazzling glory surrounded by the heavenly hosts, the seraphim

and cherubim! He was walking through the air, coming from the west door towards

the middle of the church. He stopped before the sanctuary, raised his arms and

blessed the celebrants and people. Then, transfigured, he went into his icon by

the Royal Door, still surrounded by the angelic escort which continued to

illumine the church with its shining light. As for me, who am only dust and

ashes, I was given the grace of receiving an individual blessing from the Lord

so that my heart overflowed with joy.” For those who witnessed the scene, St.

Seraphim’s expression suddenly changed, and he became rooted to the spot. Two of

the other deacons took him by the arms and brought him into the sanctuary where

he remained for two hours without being able to utter a word.

[33]

During St. Seraphim’s diaconate, another event took place that would eventually prove to be momentous for his future ministry. Starez Joseph died and Abbot Pachomius decided that he would take over as spiritual guide to St. Seraphim. As a result, during his pastoral visits to the surrounding communities, Father Pachomius would often take St. Seraphim with him. Thus it was when in June 1789, St. Seraphim met Mother Alexandra (Agathia Semenovna Melgounova) in Diveyevo.

She had gathered several women and girls around her who wanted to

live a life of prayer; and it was from what would turn out to be her death bed

that month that she extracted a promise from the abbot not to forsake her

little community. Father Pachomius answered prophetically: “Mother! I do not

refuse to serve the Heavenly Queen according to my strength and your

commandment. But how to undertake it, I do not know. Shall I live to that day?

But here is Hierodeacon Seraphim. His spirituality is known to you, and he is

young. He will live to that day. Entrust him with this great task. Mother

Alexandra answered that while she was only making a request, “the Heavenly

Queen would then instruct him herself.”

[34]

Priesthood

After being recommended for the honor by Abbot Pachomius, on

02 September 1793, St. Seraphim was ordained priest by Bishop Theophilus of

Tambov (to which diocese the monastery had recently been transferred). In this

capacity St. Seraphim served with great fervor, celebrating daily, which for

him was “A well of water springing up into everlasting life.”[35]

The importance of Eucharist to the saint is, perhaps, captured in the following

instruction he gave to the sisters of Diveyevo: “It is not right to forego the

chance to benefit as often as possible from the blessing given through the

Communion of the Holy Mysteries of Christ. Concentrate as hard as you are able,

in meek awareness of your utter sinfulness and with hope and firm faith in

God’s unspeakable mercy, upon approaching His Holy Mysteries by which He has

redeemed all and everyone. Say with tender feeling, ‘Forgive me my sins, O

Lord, that I have committed with my soul, heart, words, deeds, and all my

senses.’[36]

There can also be no doubt that the Grace bestowed by Christ through the

Apostles and down to the Priesthood St. Seraphim received by the laying on of

hands was reflected in his ministry.

Hermit

Abbot Pachomius died on 06 November 1794, and so St.

Seraphim lost another staretz. St. Seraphim said “Joseph [his first staretz]

and Pachomius were two pillars of fire with their flames leaping up to heaven.”[37]

The Elder Isaiah became his new staretz, and also took over as abbot of the

monastery. The death of Pachomius was to be a mile marker or turning point in

St. Seraphim’s life, for in just two weeks he was to leave the enclosure of the

monastery to live as a hermit in the dense woods that surrounded Sarov. From

the available biographical material, it is not clear just what the underlying

motivation was. It has been variously suggested that St. Seraphim’s desire was

because he was a “‘heavenly man’ [who] flew away to solitude ‘for God’s sake’,”[38]

because he “bitterly lamented”[39]

the loss of Pachomius, because he desired to move “deep into the desert,”[40]

because he “felt free to request permission to withdraw to a deserted part of

the forest”[41] (as if he

had been longing to do this for some time but was unwilling to leave

Pachomius), or it was because he had lost “the spiritual help which he still

needed” and “was earnestly seeking for prayer and the increasing pilgrimages to

the monastery were a hindrance to the life of silence which he loved.”[42]

It has also been suggested that he wanted to separate himself from strife

within the monastery.[43]

This last interpretation comes from advice given later by St. Seraphim to a

monk who had asked: “‘Father… people say that retirement from a community into

solitude is pharisaism and that such a change of life means disparagement of

the brethren or else their condemnation.’ To this Father Seraphim replied: ‘It

is not our business to condemn others. And we leave the Brotherhood not out of

hatred for them, but chiefly because we have accepted and wear the habit of Angels,

for whom it is unbearable to be where the Lord God is offended by word and

deed. And therefore when we separate ourselves from the Brotherhood, we only

avoid hearing and seeing what is repugnant to God’s commandments which may

happen in a multitude of brethren. We do not run away from men who are of the

same nature as we are and who bear the name of Christ, but from the sins which

they commit. As it was said to the Great Arsenius: ‘Flee from men, and thou

wilt be saved.’’”[44] The

apparent motivation was due to St. Seraphim’s poor health, for the note giving

him permission to leave read “…on account of his unfitness for life in

community, owing to his illness… .”[45]

However, St. Seraphim was very far from willful; it is better stated that the

true motivations were spiritual, and for him to make the radical shift from

life as a cenobite to that of an eremite could have only come as an

obedience—as formerly to his mother, Elder Dositheus, Elder Joseph, and

Abbot Pachomius—to his new spiritual father, Abbot Isaiah, as he, in

turn, would have been obedient to the guidance of the Holy Spirit. It should

also be noted that, in the physical realm, this was apparently somewhat “risky”

for Father Isaiah, as hermitages and sketes had been banned under Peter the

so-called “Great,” a ban that would not be lifted until 1822. (Nor was St.

Seraphim the only hermit permitted to live in the woods around Sarov.)

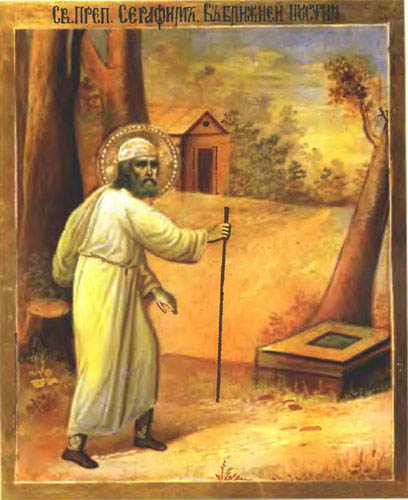

Thus it came about that on 20

November 1794, sixteen years to the day after he had first passed in through

the gates of the Sarov “Desert” bell tower, St. Seraphim passed through the

gates into a deeper “desert” and the life of a solitary. The monastery’s

“summer house” (later known as the far hermitage) into which he settled was

located some five versts (5.3 km or 3.3 miles) away along the Sarovka River.

The hermitage was a small, one-room log cabin with a porch, anteroom, and

celler. It was furnished only with stove, a wooden chopping block which served

as a chair and table, and a sack of stones for a bed.

|

|

|

In the corner opposite the stove, St. Seraphim hung an “Umilienie” icon [46] of the Theotokos—an icon he was to keep with him throughout his life (he died before it while kneeling in prayer)—and to who he dedicated the hermitage. Outside of the cabin St. Seraphim maintained a vegetable garden which, other than bread from the monastery, provided all his food. He named his new home “Mount Athos” and gave Biblical names to the surroundings.

In hermitage, St. Seraphim’s life

consisted chiefly of prayer. He usually said the Divine Office in the customary

order. He arose about midnight and recited the Midnight Service, the Orthros,

and read the First Hour. Before ten in the morning he began his reading of the

Third, Sixth, and Ninth Hours, and the Typical Psalms. The afternoon was

followed by recitation of Vespers, and after his evening meal, the Prayers

after Supper (Compline). Before retiring he said the Prayers before Sleep. St.

Seraphim also intoned the Psalms appointed by the Rule of St. Pachomius, and

read the Scriptures—especially the Gospels. “Holy writings,” he said

later, “should be read in order to free the soul to rise to the heavenly realms

and partake of the sweetest discourse with the Lord.”[47]

At all other times he continuously repeated the hesychast silent Prayer of the

Heart.[48]

His daily work consisted of tasks such as gathering moss for fertilizer and

tending his garden, chopping wood, and strengthening the banks of the river.

Later he began to carry a heavy sack filled with earth and stones, and in which

lay the Holy Gospel; St. Seraphim said that he did this, using the words of St.

Ephrem the Syrian, in order to “oppress him who oppressed me.”[49]

While he was generally separated from people during his stay in the

hermitage—only occasionally receiving visitors such as other nearby

hermits—the animals of the forest became his friends. Father Joseph

related, as an eye-witness, that rabbits, foxes, lynx, lizards, bears, and even

wolves would gather at midnight at the door of the cabin and wait for St.

Seraphim to finish his prayers and come out to feed them with bread. It has

also been related by several people that a bear would take bread from his

hands, as well as obey his orders by, for example, fetching honey when there

was a visitor.

On Saturdays and on the eve of feast days, St. Seraphim would walk to the

monastery to take part in corporate worship, including Vespers, Orthros, and

Divine Liturgy. (Although he always wore his vestments when he partook of the

Eucharist, he no longer celebrated, considering himself unworthy.) He also

spent the first week of the Great Fast at the monastery, joining his fellow

monks in prayer and in abstaining from all food. After Communion on Sundays he

would remain in the monastery until evening, receiving those who came to visit

seeking advice or consolation. He would then return to his hermitage, bringing

bread for the week.

On 09 September 1804, three men in search of money or other valuables attacked St. Seraphim. In their rage of not finding anything worthwhile, they beat him severely and left him for dead. While he could have defended himself—he was carrying an axe and was known at the time to have been a powerful man—he did not resist.

Over the

course of the next day he managed to drag himself to the monastery, suffering

from multiple injuries to his head, chest, ribs, and back. While doctors were

called for, St. Seraphim refused treatment, and fell into a semi-coma. At some

point he had another vision of the Theotokos, accompanied by the Apostles Peter

and John. “What is the use of doctors?” she said. “He is of our family.” Eight

days after the attack and a few hours after this vision, he was able to get up,

walk a little, and take some nourishment. But only after five months had passed

was St. Seraphim able to return to his hermitage (ca. February 1804), although

physically he was to remain crippled and bent over throughout the rest of his

life (as often seen in icons of the saint), which was taken as a sign of his

humility.

[50]

What can be said of this attack?

The devil, in his inability to conquer the saint through the spiritual attacks

and temptations that faced him in the preceding years, tried to overcome him in

the physical realm. When St. Seraphim was asked if he had seen demons, he was

silent and then simply said “they are despicable.” At another time St. Seraphim

related that “He who has chosen the hermit life must feel himself constantly

crucified… The hermit, tempted by the spirit of darkness, is like dead leaves

chased by the wind, like clouds driven by the storm; the demon of the desert

bears down on the hermit at about mid-day and sows restless worries in him,

distressing desires as well. These temptations can only be overcome by prayer.”[51]

In apparent response to the physical attack, however, at some point during the

year after his return to the hermitage (ca. March 1804 to March 1805), St.

Seraphim undertook what was to become his most challenging podvig: although it

was only to become known at the end of his life, he chose to undertake a

stylite-like contest, even as crippled as he was, by spending one-thousand days

and nights in prayer on a granite rock (some say 1001), only interrupting the

task for necessary care of the body (rest and food[52]);

by night he prayed on a bolder located in the forest about halfway between his

cell and the monastery, and by day on another stone that he had dragged into

his cell so as not to be seen by people. When this feat was revealed at the end

of the saint’s life, one of the brethren said in astonishment: “This is above

human strength.” St. Seraphim replied: “St. Simeon the Stylite stood for

forty-seven years on a pillar. Are my labors comparable to this?” The brother

responded that he must have been helped by grace. St. Seraphim agreed saying,

“Yes, otherwise human strength would not have been sufficient. When there is

contrition in the heart, then God is also with us.”[53]

St. Seraphim completed his work as a “stylite” at some point not too long

before Abbot Isaiah died on 04 December 1807.[54]

St. Seraphim next undertook another ascetical work: that of silence. He

remained completely cutoff from the world except for the weekly visit of a monk

who began to bring him some bread and boiled cabbage.

[55]

This mode of life in the hermitage continued until the new abbot, Niphont,

decided he would not continue to support St. Seraphim in his isolation, but

rather demanded that he resume attending services on Sundays and feast days, or

else return to the monastery. So it was that on 08 May 1810 St. Seraphim

returned from the hermitage to the monastery. However, he continued his

practice of silence and shut himself up, with permission, in his cell, only

coming out at night for short walks, and he received no visitors. Holy

Communion and food was brought to him in his cell, which he received on his

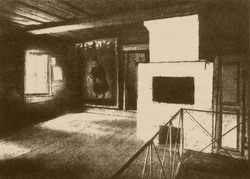

knees with his face covered with a piece of linen. The furnishings of his cell were not unlike those of the

hermitage, except for the addition of a coffin that the saint had made for

himself. As before, St. Seraphim continued to occupy himself with internal

(hesychast or Jesus) prayer and reading. To his silence he also added the

additional podvig of wearing a heavy iron cross. He was not alone, however; the

Theotokos was always present through her icon, and angels began to appear and

converse with him.

Ca. 1813 St. Seraphim began to relax his reclusion by occasionally receiving some people whom he would hear and instruct; for example, on 13 September that year the Tambov Governor A.M. Bezobrazov and his wife came, and the Elder opened his door to them himself and silently blessed them. In 1815, St. Seraphim brought an end to his isolation; monks could now enter his cell to visit, and on occasion he would receive other visitors (although, in general, he continued to practice silence); he was even visited in 1825 by Tsar Alexander I.[56]

Finally, on 25 November 1825, the Theotokos again appeared to St. Seraphim in a

vision, accompanied by St. Onuphrius the Great and St. Peter of Athos (both 12 June), and told him he was now

ready to devote himself in ministering to others.

Spiritual Father

While the Sarov Monastery was, for years, a place of

pilgrimage, news concerning the man-of-God Seraphim had spread far and wide.

People began to flow to Seraphim-as-staretz in such numbers that it disturbed

the operation of the monastery. Pilgrims rushed the gates in the morning, and

it was often impossible to shut them before midnight. As a partial relief St.

Seraphim received the blessing of the abbot to divide his time between life in

the forest and at the monastery.[57]

On his first day of “freedom” he had traveled about 1½ miles along the

Sarovka toward his original (far or distant) hermitage when the All-Holy

Theotokos appeared to him, accompanied by the Apostles Peter and John. She

beckoned to St. Seraphim, struck the ground with her staff, and a fountain of

water gushed forth from an old, long since dried up spring. The water, she told

him, had the power of healing, and she placed the spring under his care. Close

by the spring, the monks built St. Seraphim a new hut that he would call his

near hermitage.

To all who came to him he would bow

to the ground and address with the salutation “Greetings, my joy, Christ is

risen.” He would also offer them a piece of antidoron (blessed bread) dipped in

wine. St. Seraphim counseled in practical and spiritual matters, frequently

anticipating the needs and requests of suppliants. When asked about this

ability, St. Seraphim explained “They come to me and see in me a servant of

God; and I, lowly Seraphim, consider myself as His humble servant, and what God

orders His servant I transmit. I consider the first thought that comes to my

mind as sent by God. What I say is spoken without my knowing what goes on in

the heart of the person I am talking to, but in the belief that it is God’s

will and that it is for his good.”[58]

Prophet

By the very nature of his role as a staretz, the Holy Spirit

worked through St. Seraphim to guide the faithful, and this often took the form

of prophetic utterances. Many are found recorded in the various biographies of

the saint. A few selections follow.

To a Father Anthony: "You will be leaving your monastery, but you are not to die yet. Instead, you will be appointed to head a large and famous monastery elsewhere." Sometime later he was indeed appointed to serve as acting head of the Monastery of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius in Zagorsk.[59]

Regarding the Diveyevo convent:

"I entrust you to God and to our All-Holy Virgin. Have no fear. After many

trials, order will be restored to the convent with the twelfth Mother Superior,

whose name will be Mary." (see Diveyevo discussion below.) Such troubles

began during Seraphim's lifetime due to jealousy, pettiness, and intrigue on

the part of some of the fathers.[60]

It is also related that before St. Seraphim reposed, he had given a candle to

his spiritual son, N.A. Motovilov, and told him, “When my relics return to

Diveyevo, meet me with this candle.” Motovilov said in astonishment,

“Batiushka, the monks of Sarov will never give you to Diveyevo.” St. Seraphim

simply repeated that it would be so. After Motovilov’s death the candle was

passed from nun to nun until Matushka Margarita returned to the village from

prison, when it was passed on to her. When St. Seraphim’s relics arrived in

1991, having been carried for miles on the shoulders of eager pilgrims,

Matushka Margarita met her beloved elder at the gate with the lighted candle.

St. Seraphim not only predicted the monastery’s closing, but its revival as

well. Matushka Margarita says, “He said that the churches would be destroyed

for seventy years and then given back, ‘without your asking.’ But I am still

awaiting the arrival of the great Diveyevo bell that was taken away after the

monastery closed. St. Seraphim said that after the reopening of the monastery

the great bell will return overland, and at its ringing, he and the four

others, whose relics he will uncover, will arise. Soon afterwards the end will

come.”[61]

Regarding apostasy in Russia: “At

that time Russian bishops will become so ungodly that their impiety will exceed

that of the Greek bishops who lived in the reign of Theodosius the Younger.

They will not even believe in the most important dogma of the Christian Faith

the Resurrection of Christ and the general resurrection.”[62]

Regarding the fall of Russia (as

related by Countess Natalia Vladimirovna Ursova): "I knew of the prophecy

of St. Seraphim about the fall and resurrection of Russia; I knew it

personally. … Count [Y.A.] Olsufyev… once brought me a letter to read through,

with the words: 'I have preserved this as the apple of my eye.' The letter,

yellow with age, with severely faded ink, had been written by the very hand of

the holy St. Seraphim of Sarov to Motovilov. In the letter was a prophecy

concerning those horrors and misfortunes which would befall Russia, and I only

remember what was said in it about both the pardon and salvation of Russia.

…"[63]

After his repose, St. Seraphim also appeared in a prophetic vision to St. John

of Kronstadt regarding the persecutions that Christians were to undergo in

Russia.[64]

Regarding Tsar Nicholas II: St.

Seraphim of Sarov prophesied in clear words about the tragic fate foreordained

by God for the Tsar who would be present at the Savor solemnity of faith, when

there would be Pascha in the midst of summer (the glorification and

canonization of St. Seraphim in 1903). According to his prophecy, if there

would be repentance in the Russian people, God would yet have mercy on her, but

first He would allow for a time the triumph of lawless men: the Tsar would to

overthrown and killed, so that the people might know in experience what life

was like under the Tsar anointed by God, and under the rule of men who have

trampled underfoot the law of God. St. Seraphim, by revelation from God, wrote

in his own hand a letter to the Tsar who would come to Sarov and Diveyevo, entrusting

it to his friend Motovilov, who gave it to Abbess Maria, who in turn handed it

personally to Emperor Nicholas II in Diveyevo on July 20, 1903. What was

written in the letter remains a secret, but one can suppose that the holy elder

saw all that was to happen and warned against the frightful events to come... [65]

Regarding his own death, St. Seraphim said that a fire would alert the monks

about it. On Sunday, January 1st, 1833, the Starets came to church, partook of

the Holy Eucharist, and bade farewell and consoled to his fellow monks and

novices saying "Do not be dejected, be alert, the present day prepares a

crown." Three times that day he was observed to leave his cell and

meditate over the location where he had requested to be buried. He was also

heard to be intoning Easter--and not the expected Christmas--hymns. About six

o'clock the following morning, monks noticed smoke coming from under his door.

When he did not answer, they entered his cell and found a smoldering fire that

had started from a candle that had fallen from his hand after he died while

kneeling in prayer.[66]

Healer

St. Seraphim is known as a wonderworker through who God

worked many miracles of all kinds. And he still continues to work miracles,

even beyond the borders of his native land. The miracles associated with St.

Seraphim are so numerous they are far beyond recording here (for which see some

of his many biographies), and God alone knows of all those unrecorded. However,

as an illustration, two healings are presented here for God’s Glory.

In 1822, before St. Seraphim had completely ended his reclusion, Michael

Vasileevich Manturov came to see him in the hope that God would help where

doctors could not. Michael Vasileevich had served in the Russian military in

Lithuania for many years. While there he had contracted some form of wasting

disease in his legs, and was eventually forced to resign and return to his home

that lay ~25 miles (40 km) from Sarov. However, the best of medical help was

unable to discern what was wrong, let alone provide a cure.

When the disease progressed to the point that pieces of bone dropped from his

legs he became determined to see St. Seraphim. He was carried by his serfs to

the cell of the then reclusive saint. After Michael Vasileevich made the customary

prayer, St. Seraphim came out and kindly asked “what brings you to see poor

Seraphim?” Manturov fell at his feet and begged the Elder to heal him. St.

Seraphim asked him three times, “Do Vasileevich responded each time with a

strong, positive affirmative. St. Seraphim said to him “My joy, if you so

believe, then believe also that to the faithful everything is possible to God;

and so believe that God will also heal you, and I, poor Seraphim, shall pray.”[67]

The saint then took some oil from the lamp burning in front of the Icon of the

Virgin in his cell and anointed Manturov’s legs, wrapped them in pieces of

canvas, and said “By the grace given me from the Lord, you are the first whom I

heal.” St. Seraphim then stuffed handfuls of blessed bread into Manturov’s

pockets and told him to return to the monastery guest house. The invalid, who

normally could hardly stand, began to carry out this order, then realizing that

he was walking without help, returned to the saint and fell at his feet in

thanksgiving. St. Seraphim picked him up and said “Is this healing Seraphim’s

doing? No, no, my joy, only God does this, and you owe your cure to Him and his

holy Mother.”[68] Later, in

thanksgiving, Manturov was to sell his lands, free his serfs, move to Diveyevo,

and there serve St. Seraphim until 1831 as an intermediary with the sisters.

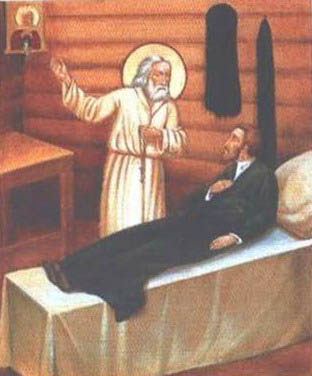

On the 9th of September, 1831, Nicholas Alexandrovich

Motovilov—a man also destined to help Diveyevo—was laid at the feet

of St. Seraphim. “One year before he commanded me to serve the Mother of God in

Diveyevo Convent, the great Elder Seraphim healed me from serious and

extraordinary rheumatic and other illnesses, a weakening of the entire body and

the loss of the use of my legs, which were contorted, and swollen knees, with

sores upon the sides and back. From such a disease did I suffer incurably for

more than three years. In 1831, on the ninth of September, Fr. Seraphim healed

me of all my diseases with only one word. The healing occurred in this way. At

my request for help and healing, he said, ‘I am not a doctor; you must go to a

doctor to be cured of any kind of illness.’ I gave him a detailed account of

all my calamities, about the three major medical methods I had tried… But by

none of thee methods was I cured of my diseases, and so I realized that I could

not be healed of my ailments by any means save the grace of God. But being a

sinner and not having boldness before the Lord God, I asked for his [St.

Seraphim’s] holy prayers, that God would heal me. He then asked me a question,

‘Do you believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, the He is God incarnate, and in the

Most Pure Mother of God, that she is the Immaculate Virgin[69]?’

I answered, ‘I believe.’ ‘And do you believe,’ he continued to ask me, ‘that

the Lord instantly healed with one word, or with His touch, all such diseases

as the people had, and so can even now, just as easily and instantly as before,

heal all who ask His help, with His same one word, and that an entreaty to Him

by the Mother of God for us is all-powerful, and that by her entreaties the

Lord Jesus Christ can even now, this instant, heal you completely?’ I answered,

‘I trust with all my heart and believe it, and if I did not believe it, then I

would not have asked them to bring me to you.’ ‘If you believe,’ he concluded,

‘then you are healed already.’ ‘How can I be healed,’ I asked, ‘when my people

and you yourself hold me in your arms?’ ‘No,’ he said to me, ‘your entire body

is perfectly healthy at last.’ He ordered those who were holding me in their

arms to step away… I felt within me some kind of power descending upon me from

on high, I lightened up a little and walked… Then he talked with me a good deal

more, and sent me off to the guest house completely restored. And so, my people

left without me… thanking God for His wondrous mercy shown to me before their

very eyes. …”[70]

Director

In 1780, in the small village of

Diveyevo[71]

that is located about 12 km (7 mi) NNW of Sarov, a wealthy widow by the name

Agathia Semenovna Melgounova (or Agatha Melgunova)—later Mother

Alexandra—built a church and received permission to set up a women’s

community. On her death bed in 1789, as previously related, she asked Abbot Pachomius

not to forsake her little community, and who, in return, offered up St.

Seraphim as one suitable to be so entrusted. It was not until 1823, however,

that St. Seraphim took a visibly active role in the community. In that year he

asked Michael Manturov (who had been healed the previous year) to stake out

some land near the church that Mother Alexandra had built. A year later a new

community was formed there; it differed from the adjacent convent formed by

Mother Alexandra in that only virgins (i.e., no widows) were allowed there. The

Theotokos was considered to be their Abbess. A church was built for the convent

by Manturov in 1829 and consecrated on the Feast of the Transfiguration (06

August). St. Seraphim gave the sisters a simple rule involving obedience,

prayer, and regular attendance at the Divine Liturgy. Since the sisters worked

in the fields and in operating a mill, he discouraged undue fasting.

St. Seraphim also provided for the

sisters spiritual and material welfare. Although he never personally visited

the convent, the sisters would visit St. Seraphim at the Sarov monastery or in

one of the hermitages; on such visits they would receive the spiritual guidance

required as well as bags of provisions. At times, these visits became

opportunities to witness various wonders or miracles; for example, Sister

Eupraxia (Eudoxia Ephraimovna) was to share in the twelfth (and last) visit of

the Theotokos to St. Seraphim. This occurred on the eve of the Feast of the

Annunciation (24 March) in 1831. After having prayed through the night, a sound

was heard at dawn like a wind rising in the forest, which turned into singing

as it grew closer. St. Seraphim told Eupraxia, “Do not be afraid. Behold the

Lord’s grace coming down to us.” The air became scented as the richest incense.

St. Seraphim raised his arms and then fell prostrate crying out “O, most holy

Theotokos!” Eupraxia then saw two angels enter, preceding the entrance of the

Queen of Heaven. Accompanying the Theotokos were the Apostles John and Peter,

and with them twelve virgin-martyrs, each with a crown. The cell was lit with

such a brilliant light that Eupraxia was dazed and fainted. The Theotokos,

herself, raised Eupraxia up, and presented her to the holy martyrs. Eupraxia

also recalled hearing the Theotokos tell St. Seraphim “Soon, my dear one, you

shall be with us.” The vision lasted four hours![72]

After St. Seraphim died, his

spiritual presence continued to be felt in Diveyevo, and in all their

difficulties they turned to him for spiritual help. Every evening the sisters

would gather around a candle and recount some detail of the Staretz’ life, and

the saint seemed to join their circle and fill their hearts with comfort and

joy. On a few occasions, St. Seraphim actually appeared to some of the sisters.

For example, on New Year’s Eve 1835, one of the sisters went to the church to

pray and saw St. Seraphim dressed in white vestments coming to meet her. “Is it

you, Little Father?” she asked. “Of course it is, my joy. Don’t you recognize

me? Yet you go on calling me. O how unbelieving you are. Don’t you realize by

now that I’m celebrating with you in the church every day?” The saint then

returned to the sanctuary through the Beautiful Gate.[73]

However, although the Theotokos and

St. Seraphim continued to spiritually watch over the community, the troubles

that the saint had prophesied about came to pass. A certain Ivan Tikhonovitch portrayed

himself (falsely) as a disciple of St. Seraphim, and was able to gain influence

and control of the Diveyevo communities. In 1842 he was able to obtain

permission to amalgamate the communities (thc one started by Mother Alexander

with the “mill” community or “orphans” of St. Seraphim). He then built a new

church according to his taste, closed those of St. Seraphim, and replaced most

of the other structures as well. By 1848 Ivan decided to build a cathedral at

Diveyevo, although not according to St. Seraphim’s design or location, but

following after his own thoughts. However, when Archbishop Jacob of

Nijni-Novgorod came to bless the work on 14 June 1848, Michael Manturov was

able to lay before him all of St. Seraphim’s plans. The archbishop, thoroughly

upset, went to the site where Ivan had begun digging the foundations,

and—like the Old Testament Balaam who had blessed Israel instead of

cursing her—he spoke blessings on the plans of St. Seraphim and not those

of Ivan: “May the Lord bless this foundation on the spot which Father Seraphim

foresaw and which Michael Manturov has shown me.”[74]

In 1858, after Manturov died, Ivan (now known as Father Joseph), thinking

himself free from all rivalry, began anew to machinate concerning Diveyevo.

When it was announced in 1861 that the community had been promoted to the rank

of monastery, Father Joseph worked through his friend, Archbishop Nectary of

Nijini-Novgorod to depose the then duly elected (by the sisters) superior

Elizabeth as being unworthy, and set up sister Glykeria—who was loyal to

Joseph—in her place. With Manturov gone, Nicholas Motovilov—the

very one who, like Manturov, had been healed through the prayers of the

saint—now took up “arms” to protect Seraphim’s “orphans”. Motovilov

brought the affair to the attention of Metropolitan Philaret through the agency

of Archimandrite Anthony, Abbot of the Monastery of the Holy Trinity-St.

Sergius in Zagorsk (as St. Seraphim had prophesied). Metropolitan Philaret, in

turn, briefed Tsar Alexander II concerning the situation in Diveyevo, who then

launched a full investigation. The end result was that the community of

Diveyevo was placed under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Tambov,

Archbishop Nectary was transferred, Joseph was forbidden to set foot in the community

again, Joseph’s supporters were sent away, and sister Elizabeth took the great

habit under the name Mary and was installed as the twelfth

superior—fulfilling another prophecy of St. Seraphim.

Teachings

Although it can be stated that St. Seraphim was certainly literate, he did not write any theological treatises or spiritual works. What teachings of the saint we have were principally recorded by the monks of Sarov, and in particular Hieromonk Gury. [75] Circa 1837 the first biography of St. Seraphim was compiled by Hieromonk Serge (Sergius) of the Monastery of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius in Zagorsk (presumably by the direction of Archimandrite Anthony). As a supplement to this Life, Serge included 33 counsels or instructions of the saint; these were eventually edited by Metropolitan Philaret and published in an appendix to Father Serge’s Short Sketch of the Life of Starets Mark, Monk and Hermit of the Monastery of Sarov. A expanded collection of 43 instructions was published as part of Leonid Denissov’s work Zhitie prepodobnavo ottsa nashevo Seraphima Sarovskavo in 1904. Selections and digests of these instructions can be found in most biographies of the saint. The complete set is available in English in Volume One of the Little Russian Philokalia. [76] These instructions give indisputable evidence of St. Seraphim’s knowledge of the Philokalia and the whole Hesychast tradition, as well as a deeply personal life with Christ in the Holy Spirit.

But perhaps the most important

thing we have from the saint is known by various titles such as “a conversation

with the saint” and “on the acquisition of the Holy Spirit;” this, too, appears

in most biographies of the saint. This conversation took place with Nicholas

Motovilov in November 1831. “… when you were a child… They instructed you to go

to church, to pray, to do good works, telling you that there lay the goal of

the Christian life. … Prayer, fasting, works of mercy—all this is very

good, but it represents only the means, not the end of the Christian life. The

true end is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit. … You know what it means to

earn money, don’t you? Well, it is the same with the Holy Spirit. The aim of

some men is to grow rich, to receive honors and distinctions. The Holy Spirit

himself is also capital, but eternal capital. Our Lord compares our life to

trading and the works of this life to buying: ‘Buy from me gold…that you may be

rich’ (Rev. 3:18). … The only valuables on earth are good works done for

Christ: these win us the grace of the Holy Spirit. No good works can bring us

the fruits of the Holy Spirit unless they are done for love of Christ. That is

why the Lord himself said, ‘He who does not gather with me, scatters’ (Matt.

12:30). In the parable of the virgins, it was said to the foolish virgins when

they had no oil: ‘Go to the dealers and buy’ (Matt. 25:1-12). … What…could be

termed lacking when…they had preserved their virginity…one of the greatest

virtues… I dare to think that what they were lacking was the grace of the Holy

Spirit. For the essential thing is not just to do good but to acquire the Holy

Spirit as the one eternal treasure which will never pass away. … Among works

done for the love of Christ, prayer is the one that most readily obtains the

grace of the Holy Spirit, because…it is within reach of all men…” Toward the

middle of this conversation, both St. Seraphim and Motovilov became illumined,

much as Moses of the Old Testament after he came down from Mount Sinai (Ex.

34:29-35). Motovilov related: “Then I looked at the Staretz and was panic-stricken.

Picture, in the sun’s orb, in the most dazzling brightness of its noon-day

shining, the face of a man who is talking to you. You see his lips moving, the

expression in his eyes, you hear his voice, you feel his arms round your

shoulders, and yet you see neither his arms, nor his body, nor his face, you

lose all sense of your self, you can see only the blinding light which spreads

everywhere, lighting up the layer of snow covering the glade, and igniting the

flakes that are falling onus both like white powder. …this ineffable light went

on shining all the time he was talking.”[77]

Death

As noted earlier, St. Seraphim had prophesied concerning the

circumstances of his death. About six in the morning, January 2nd,

1833, Hieromonk Paul of the Sarov monastery, on his way to attend the early

Liturgy, smelled smoke as he passed by the cell of St. Seraphim. As there was

no response from his knock at the door—which was latched from the

inside—he went outside and told some of the brethren who were passing by.

The Novice Anikita was able to break the door from its hinges.

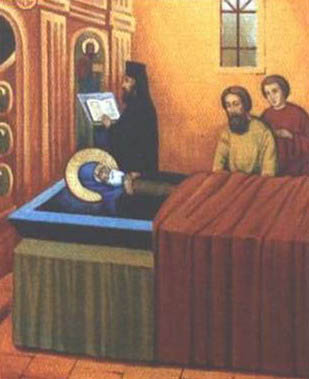

On entering the cell the monks found that some coarse linen was smoldering,

probably as a result of a fallen candle. St. Seraphim was found kneeling before

the “Umilienie” icon, wearing his usual white smock, bare headed, with the

brass crucifix his mother had given him hanging from his neck, and with his

arms crossed.

The monks prepared St. Seraphim for burial according to monastic regulations, placed him in the oak coffin he had made, placed an enameled icon of St. Sergius with him according to his request, and carried him into the Cathedral where it remained for eight days and nights until all had had time to bid him farewell.

|

|

The news of his death spread

quickly, and thousands of people gathered from the surrounding provinces.

On the day of his burial there was such a throng of people in the Cathedral

that the candles melted from the heat. St. Seraphim was buried on the south

side of the sanctuary of the Cathedral, beside the grave of the recluse Mark

who died fifteen years before him.

Among others, the following two

miracles are associated with St. Seraphim’s death. On January 2nd,

Abbot Philaret of the Glinsky Monastery of the Mother of God, Province of Kursk

(now the Sumy Oblast, Ukraine), went out of the church after Matins and,

glancing up at the sky, he was astonished to see an extraordinary light. Then

the abbot saw in the spirit what the sign meant and related to those who were

with him: “That is how the souls of the righteous depart. Father Seraphim has

just passed away in Sarov.” Nicholas Motovilov also recorded this in his

memoirs: “On the 2nd of January in the evening I heard from

Archbishop Antony [of Voronezh] that Father Seraphim had passed away on the

previous night at 2 a.m. and that apparently he (St. Seraphim) had himself

appeared to him and informed him of it. On the very same day Archbishop Antony

served a Pannikhida for the Elder with all the Cathedral clergy.”[78]

It should be noted that both the Glinsky Monastery and the Voronezh Cathedral

were hundreds of kilometers away from Sarov, and that, in those days, there was

no physical way for such news to have traveled so fast.

Consecration [79] , [80] , [81]

After the death of St. Seraphim, the flow of pilgrims to

Sarov increased. Many miracles were registered in the Sarov archives, which

were certified by witnesses. Many others were not; it is reported that Sarov

Abbot Hierotheus did not desire to write down the thousands of accounts of help

from the saint—there were simply to many of them. The area surrounding

Sarov was especially full of stories of St. Seraphim and his miracles, and

there was no house wherein a traveler did not hear of “our Batiushka.” From the

moment of his death people began to serve Pannikhidas for him, and icons of his

likeness could be frequently seen. For most people, the sanctity of St.

Seraphim was not in question; it only remained for church authority to

recognize this fact. The first person to officially begin inquiries in this

direction was Archimandrite Raphael, the Sarov superior, ca. 1883; a special

commission gathered materials about Seraphim’s life and miracles, and presented

them to the Tambov Ecclesiastical Consistory. In 1892 the Holy Synod

commissioned an official inquiry into the Staretz’ life and miracles; 28

departments from across all of Russia reported about one hundred miracles that

had been registered. In 1903, Tsar Nicholas II approved a resolution of the

Holy Synod to form another commission under the direction of Metropolitan Vladimir of Moscow. That

the Tsar had a personal interest in seeing that the inquiry be brought to a

conclusion was understandable in that St. Seraphim had long had a special tie

to the Russian Royal Family. The personal relationship between the great-great

uncle of Tsar Nicholas II—that is Tsar Alexander I—has already been

mentioned. Furthermore, Nicholas’ great grandmother Alexandra Feodorovna

(Charlotte of Prussia) received healing due to the intercessions of the saint.

A grand duchess had also been healed through his prayers.

Thus it came about that in January

1903 the commission came to Sarov to proceed with the exhumation of the

Staretz’ body. The cavity was opened and was found to be full of water, but the

oak coffin was reasonably intact. When the coffin was opened, the body of

Seraphim was found therein, still wrapped in his monastic cloak. The bones had

a brownish hue, his hair exhibited a reddish-brown tinge, and his brass cross

rested intact on his breast. The coffin was closed again and tilted to allow

the water to drain away and remains to dry out. On the 5th of July

it was brought to the infirmary church for the ablution of the relics; during

this rite a scent of flowers and honey was noticed. The precious relics were

then placed in an oak coffin that replicated the original.

In preparation for the solemn

glorification of St. Seraphim special preparations were taken by the civil

authorities to handle the expected influx of pilgrims. It should be recognized

that Sarov is located in a remote, dense forest and, at the time, the nearest

village was over 6 km (4 miles) away. Hundreds of huts, rows of shops, and even

supporting chapels, were built along the roads leading into Sarov. Records

indicate that over 200,000 pilgrims came for the services from across the Russian

empire.

The last Offices for the repose of

Father Seraphim’s soul began at 5 a.m. on July 18th, and at 6 p.m.

the great cathedral bell tolled for the beginning of Vespers, during which the

Staretz was to be glorified as a saint for the first time. This included a

solemn procession where the celebrants, followed by the imperial couple (Tsar

Nicholas-II and Tsarina Alexandra) and all the faithful, made their way from

the cathedral to the infirmary church. The coffin containing the holy relics

was censed, placed on a litter, and borne on the shoulders of bishops, priests,

and the Tsar himself, back into the cathedral.

When the office was over the

cathedral was left open all night so that the crowds could approach the coffin.

The next morning, the anniversary of St. Seraphim’s birth, the relics were

placed in a marble shrine with a silver cover bearing seraphim at each corner,

and then a new procession wound through the roads of Sarov.

During the services and processions

associated with St. Seraphim’s glorification, many healings were recorded. It

has also been reported that while the imperial couple were in Sarov on this

occasion, that the Tsarina bathed in the miraculous waters of St. Seraphim’s

spring and prayed to the Saint for the blessing of a son (the Tsarevich Alexei

Nikolaevich Romanov would be conceived later in December of that same year).

Postscript

Twenty years after his canonization, the Soviets occupied

the Sarov monastery and desecrated everything. St. Seraphim’s relics were

placed in a crate and transported off to an anti-religious museum, where they

lay hidden (but not forgotten) for 70 years. In 1990 the relics were found. In

1991, in a 450-mile-long procession they were taken to Diveyevo (Sarov was part

of a security area that was off limits to the general public). Thus another one

of St. Seraphim’s prophecies was fulfilled.