The Orthodox Prayer Rope

Prologue

In the Orthodox Church, a prayer rope is an almost indispensable aid for the individual Christian in the practice of private prayer and spiritual growth, particularly in reciting the Jesus Prayer. While the use of a prayer rope is not required, it is certainly recommended. However, it must be understood that the prayer rope is not an amulet—nor is the Jesus Prayer a mantra—but a means to focus one’s attention on prayer. By keeping a prayer rope with you everywhere and at all times, it serves as an ever-present reminder to pray without ceasing. By holding a prayer rope during prayer, it serves as a means to help overcome distraction. By counting with a prayer rope—specifically in terms of the number of times the “Jesus Prayer” is said—it is a way to fulfill a prayer rule.

While the details may be murky, historically the Orthodox prayer rope appears along with the rise of monasticism in Egypt in the Third or Fourth Century A.D. The use of a prayer rope was first fostered by angelic visitations. Furthermore, a Biblical type (prophetic symbol) for the prayer rope is found in the sling that King David used to kill Goliath. And it almost goes without saying that the Jesus Prayer that is so central to the use of the prayer rope is exemplified many times over in Scripture.

Introduction

In Church Tradition, a prayer rope is used to assist the individual worshipper in their performance of various types of prayer, as will be outlined below. In all such cases, it is intimately tied with and used to recite the Jesus Prayer, either vocally or silently (Prayer of the Heart). Simply put, integral to the prayer rope are a number of knots, and for each knot the Jesus Prayer is said. Repeating the prayer a large number of times (preferably continually!) as a part of personal ascetic practice is an integral part of the eremitic tradition of prayer known as Hesychasm (Greek: ἡσυχάζω, hesychazo, “to keep stillness”).

Because of the close tie between an Orthodox prayer rope and the Jesus Prayer, a few words in regards to the prayer itself are in order. In its simplest form, the Jesus Prayer is just calling out His Name: Jesus! Eleven Scripture verses in the New Testament refer to and associate power and authority with the name of Jesus, while thirteen more do so for the name of the Lord; consider, for example:

Wherefore God also exalted Him exceedingly, and freely gave to Him a name that is above every name, that in the name of Jesus every knee should bow…(Phil. 2:10 [1] )

…whosoever shall call upon the name of the Lord, shall be saved. (Rom. 10:13)

Furthermore, this idea is exemplified in Scripture multiple times, such as when blind men (Matt. 9:27, Matt. 20:30-31, Mark 10:47-48, Luke 18:38-39) and a distraught mother (Matt. 15:22) called out to Him variously as Son of David, Lord Son of David, or Jesus Son of David, with a plea for mercy. It might also be noted that this prayer is very similar to that of the publican: “God, be gracious to me the sinner” (Luke 18:13).

|

|

|

Healing

of the two blind men. |

Christ

heals the Canaanite woman’s daughter. |

The

Publican and the Pharisee. |

| Virgin Nativity Cathedral of the St. Ferapont Monastery, Belozersk, by Dionisy in1502. Commemorated on the 7th Sunday after Pentecost. | Provenance unknown. Commemorated on the 17th Sunday after Pentecost (also the Sunday before the Triodion begins when there are four Sundays between the Sunday after Theophany and the First Sunday of the Triodion). | Virgin Nativity Cathedral of the St. Ferapont (Therapont) Monastery, Belozersk, by Dionisy in 1502. Commemorated on the first Sunday of the Triodion. |

Consider, for example, Luke 18:38, in the Greek, includes the following five word phrase: ∆Ihsouv ui˚e« Daui÷d, e˙le÷hso/n me; in English this translates as (1) Jesus (2) Son-of (3) David (4) have-Mercy-on (5) me. By replacing David with God in this phrase in confession that Jesus is God’s Son (cf. 1 John 4:15), we have ∆Ihsouv ui˚e« Θεοῦ , e˙le÷hso/n me (or Jesus Son of God have Mercy on me), which can be considered to be the most basic form of the Jesus Prayer as it has been handed down by the Church Fathers. (For reference, in Russian this phrase remains five words long as in the Greek: Иисусе, Сыне Божий, помилуй мя.) Other variations of this prayer exist—such as Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have Mercy on me—but that is another subject.

The Prayer Rope & Prayer of the Heart

Turning back to the discussion on the use of a prayer rope, we will begin by considering private, or interior, prayer—the Prayer of the Heart. The Scriptural motivation for such prayer is perhaps best typified by the injunctions of the Apostle Paul:

Be persevering in prayer… (Colossians 4:2)

…be praying unceasingly. (1 Thessalonians 5:17)

This is not unlike what King David had to say:

I will bless the Lord at all times, His praise shall continually be in my mouth. (Ps 33:1)

Achieving such a goal—continuous prayer—is what the practice of hesychasm (“stillness”) is intended to help one to achieve (see, for example, the Philokalia, the Ladder of Divine Ascent, the collected works of St. Symeon the New Theologian, and the works of St. Isaac the Syrian). However, one big problem that affects everyone—except perhaps for the most spiritually advanced—is the distraction that comes at us from all sides, physical and spiritual. In the words of several Church Fathers:

|

Until we have acquired genuine prayer, we are like people teaching children to begin to walk. Try to lift up, or rather, to enclose your thought within the words or your prayer, and if in its infant state it wearies and falls, lift it up again. …If you constantly train your mind never to wander, then it will be near you during meals too. But if it wanders unrestrained, then it will never stay beside you. A great practiser of high and perfect prayer says: ‘I wish to speak five words with my understanding,’ and so on. But such prayer is foreign to infant souls. (St. John Climacus [ca. 525-606], [2] with a quote from 1 Corinthians 14:19). |

St. John Climacus |

| If you pray with your lips but your mind wanders, how do you benefit? ‘When one buildeth, and another pulleth down, what profit have they then but labour?’ As you labour with your body, so you must labour with your intellect, lest you appear righteous in the body while your heart is filled with every form of injustice and impurity. St. Paul confirms this when he says that if he prays with his tongue—that is, with his lips—his spirit or his voice prays, but his intellect is unproductive: ‘I will pray with the spirit, and I will pray also with the understanding.’ And he adds, ‘…I wish to speak five words with my understanding,…than myriads of words in a tongue.’ (St. Gregory of Sinai [ca. 1260s-1346], [3] with quotes from Ecclesiasticus (the Wisdom of Sirach) 31:23 [4] and 1 Corinthians 14:15,19). |

|

St. Gregory of Sinai |

The Apostle Paul’s “five words”—as quoted here by St. John Climacus and St. Gregory of Sinai—is generally understood by hesychasts as reference to use of the Jesus Prayer, such as given above. But what guidance do the Fathers have concerning training for our wandering mind? St. Anthony the Great [ca. 251-356]—the “father of all monastics”—too, wrestled with this problem, out of which came a solution.

When the holy Abba Anthony lived in the desert he was beset by accidie [lethargy] and attacked by many sinful thoughts. He said to God, ‘Lord, I want to be saved, but these thoughts do not leave me alone; what shall I do in my affliction? How can I be saved?’ A short while afterwards, when he got up to go out, Anthony saw a man like himself sitting at his work, getting up from his work to pray, then sitting down and plaiting a rope, then getting up again to pray. It was an angel of the Lord sent to correct and reassure him. He heard the angel saying to him, ‘Do this and you will be saved.’ At these words, Anthony was filled with joy and courage. He did this, and he was saved. [5]

St. Anthony the Great. [6]

One interpretation of this story is that it represents the origin of the prayer rope: guidance sent from Heaven to the Father of all monks! This, however, is not the only angelic visitation associated with the prayer rope. St. Pachomius the Great [7] [ca. 292-346]—a Desert Father from the Thebaid and the “founder of cenobitic monasticism”—was visited by an angel who gave him direction to form a community, along with rules to govern it by. [8] One of these rules addressed the prayer life to be followed by the monks. The version of this prayer rule handed down through the Slavic tradition reads as follows: [9]

Begin with the Trisagion. After the Our Father: Lord, have mercy [12]. Glory, Both now: O come, let us worship , thrice. Psalm L, Have mercy upon me, O God; I believe in one God; one hundred prayers, O Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me, a sinner. And then, It is truly meet , and the Dismissal. And this is one prayer. It is commanded to perform twelve of these in the day, and twelve at night.

An Angel Delivers the Monastic Rule to St. Pachomius the Great.

Fresco by Andrei Rublev ca. 1400, Assumption Cathedral on the Gorodok, Zvenigorod, Russia

There is an obvious question concerning this rule: how is one to keep track of the number of times the Jesus Prayer is said? Paul “the Simple” of Pherme (Ferme), a disciple of St. Anthony, used pebbles to count the 300 prayers he said daily (as discussed further below). [10] While this may be functional, it does not seem very practical. The obvious answer—following after tradition—is with a prayer rope. In fact, there is archaeological evidence in the form of grave goods from the 3rd-4th Century A.D. Antinoë [11] that beaded prayer ropes, [12] at least, were in use in Egypt contemporaneous with St. Anthony and St. Pachomius.

Finally, there is a third story involving an angelic visitation and the traditional method of making an Orthodox prayer rope: “The story is told of a monk who decided to make knots in a rope, which he could use in carrying out his daily rule of prayer. But the devil kept untying the knots he made in the rope, frustrating the poor monk's efforts. Then an angel appeared and taught the monk a special kind of knot that consists of ties of interlocked crosses, and these knots the devil was unable to unravel.” [13]

But there is an earlier, Biblical type (prophetic symbol) of the prayer rope that is found in the story of David and Goliath (see 1 Kings 17 LXX; 1 Samuel 17 KJV). When St. David [ca. 1040–970 B.C.; commemorated on the Sunday falling on 11 December or the first Sunday after the 11th along with the Holy Forefathers, and on the Sunday before Nativity of Christ along with the Holy Fathers] went out to slay the giant Goliath, he took a sling and five stones. As a type, the five stones represent the five words of the Jesus Prayer, while the sling represents (and even resembles) a prayer rope. This typing becomes even stronger if we recall the words that David spoke to Goliath:

And David said to the Philistine, Thou comest to me with sword, and with spear, and with shield; but I come to thee in the name of the Lord God of hosts [emphasis added] …And all this assembly shall know that the Lord delivers not by sword or spear, for the battle is the Lord’s, … (1 Kings 17:45-47)

David and Goliath.

Byzantine plate, ca. 628-630 (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Carrying this to the spiritual level—perhaps beginning by imagining the prayer rope hanging at your side as casting a shadow not unlike a sword—it should not take too much to see the prayer rope “sling” loaded with Jesus Prayer “stones” as being part of our arsenal that will help in waging spiritual warfare.

Put on the full armor of God, for you to be able to stand against the wiles of the devil; because for us the wrestling is not against blood and flesh, but against the principalities, against the powers, against the cosmic rulers of the darkness of this age, against spiritual hosts of evil on account of the heavenly things. For this cause take up the full armor of God, in order that ye might be able to withstand in the day, and having counteracted all things, to stand. Stand therefore, having girt your loins with truth, and having put on for yourselves the breastplate of righteousness, and having shod your feet in readiness of the Gospel of peace; on the whole, take up the shield of faith, with which ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the evil one. And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God—by means of every prayer and entreaty, praying in every season in the Spirit, and being vigilant toward this same thing with all perseverance and entreaty for all the saints, [emphasis added] (Ephesians 6:11-18).

While this Scripture provides a clear connection between sword and prayer (the emphasized text), a closer reading of the text is instructive. Since we know that salvation can only be found in the name of Jesus Christ (cf. Acts 4:10-12), and that He is the Head of the Church and we are the body (cf. Eph 5:22-33), we can understand that the helmet of salvation refers to Jesus. Scripturally, it is also true that the word of God can be a reference to Jesus Christ (cf. John 1:1-5), Therefore we can interpret the last verse quoted above as referring to prayer that calls on Jesus.

|

|

But there is more. Consider St. John Chrysostom’s commentary on this Scripture:

So here we have another injunction from the Apostle Paul to be in continual prayer (as in 1 Thessalonians 5:17 and Colossians 4:2 quoted above)—specifically calling on Jesus—as part of the armor we need (sword and helmet) to defend ourselves from evil. This sounds a lot like what the Jesus Prayer and prayer rope have to offer! |

St. John Chrysostom |

The connection between a sword, the Jesus Prayer, and spiritual warfare is also found explicitly stated in the liturgical material (specifically, the Euchologion) of the Church. When a monk is tonsured into the Order of the Great and Angelical Schema, at one point in the service he is given a prayer rope with these words:

Our Brother, N. taketh the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, for continual prayer to Jesus; for thou must always have the Name of the Lord Jesus in thy mind, in thy heart, and on thy lips, ever saying: Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me. And know that thou must ever henceforth have the word of God upon thy lips, in prayer, in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs; and may no vain words go forth out of thy mouth; [15]

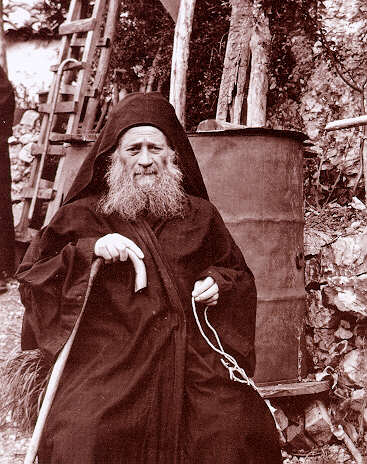

Hieroschemamonk Ephrem of Valaam with prayer rope ca. 1900. [16]

In summary to this point, we can see that the prayer rope is an important tool in helping to train us up in constant, undistracted, interior prayer—spiritual warfare—as we are called to do by the Holy Scriptures and Church Fathers.

The Prayer Rope & Liturgical Prayer

Now we will turn the discussion to the use of the prayer rope in liturgical or corporate prayer. In both Old Testament and New Testament times, it was a custom to pray, privately or publicly, at fixed times. Consider, for example, the following quotes from Scripture:

…three times in the day he [Daniel] knelt upon his knees, and prayed and gave thanks before his God… (Dan 6:10)

As for me, unto God have I cried, and the Lord hearkened unto me. Evening, morning, and noonday will I tell of it and will declare it, and He will hear my voice. (Ps 54:18-19)

Seven times a day have I praised Thee for the judgments of Thy righteousness. (Ps 118:164)

And having risen up very early at night [i.e., in the very early morning], He [Jesus] went out and departed into a desolate place, and was praying there. (Mark 1:35)

And after He dismissed the crowds, He went up into the mountain apart to pray. And evening having come to pass, He was there alone. (Matt 14:23)

…and He [Jesus] was passing the night in prayer [vigil] to God. (Luke 6:12)

And while the day of Pentecost was being fulfilled, they were all with one accord in the same place... the third hour of the day. (Acts 2:1-15)

And… Peter went up on the housetop to pray, about the sixth hour. (Acts 10:9)

And Cornelius said, “Four days ago I was fasting until this hour, and I was keeping the ninth hour of prayer in my house; …” (Acts 10:30)

And at midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God; … (Acts 16:25)

While we can say little or nothing regarding the specific content of the prayers and praise on these particular occasions, Scripture does provide a brief, general description of the types of liturgical material in use:

Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, in all wisdom, teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual odes, singing with grace in your heart to the Lord. (Col 3:16)

…keep on being filled with the Spirit, speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and chanting in your heart to the Lord, giving thanks always for all things to the God and Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, (Eph 5:18-20)

… Whenever ye come together, each one of you hath a psalm, hath a teaching, hath a tongue, hath a revelation, hath an interpretation. (1 Cor 14:26)

It probably comes as no surprise that the practice of liturgical prayer at fixed times through the day is also well attested to by the early Church Fathers. For example:

One time when he [Pachomius] was sitting in his cave an angel appeared to him and told him: ‘…call the young monks together… Rule them by the model which I am now giving you.’ … He commanded that they pray twelve prayers each day and twelve at lamp-lighting time, and that at all-night devotions they say twelve prayers, and three at the ninth hour. When the group was about to eat, he commanded them to sing a psalm in addition to each prayer. (“Pachomius and the Tabennesiotes” [17] )

|

What then is more blessed than to imitate on earth the anthems of angels’ choirs; to hasten to prayer at the very break of day, and to worship our Creator with hymns and songs; (St. Basil, Letter to Gregory of Nazianzus

[18]

)

Prayers are recited early in the morning so that the first movements of the soul and the mind may be consecrated to God… Again at the third hour the brethren must assemble and betake themselves to prayer, … It is also our judgment that prayer is necessary at the sixth hour, in imitation of the saints… The ninth hour, however, was appointed as a compulsory time for prayer by the Apostles themselves… When the day’s work is ended, thanksgiving should be offered for what has been granted us… Again at nightfall, we must ask that our rest be sinless and untroubled by dreams. … Paul and Silas, furthermore, have handed down to us the practice of compulsory prayer at midnight, … Moreover, I think that variety and diversity in the prayers and psalms recited at appointed hours are desirable for the reason that routine and boredom, somehow, often cause distraction in the soul, while by change and variety in the psalmody and prayers said at the stated hours it is refreshed in devotion and renewed in sobriety. (St. Basil, The Long Rules, “Question 37” [19] ) |

St. Basil the Great |

…at the crowing of the cock… they stand up, and sing the prophetic hymns with much harmony, and well composed tunes. … And the Psalms of David, that cause fountains of tears to flow… express[ing] their ardent love to God. And… they sing with the Angels, (for Angels too are singing then,) “Praise ye the Lord from the Heavens.” … [Afterwards] these holy men, having performed their morning prayers and hymns, proceed to the reading of the Scriptures. … Then at the third, sixth, and ninth hours, and in the evening, they perform their devotions… with psalms and hymns, … After their meal they again pursue the same course, having previously given themselves a while to sleep. … Then after sitting a short time, or rather after concluding all with hymns, they each go to rest upon a bed made for repose only and not for luxury. (St. John Chrysostom, “Homily XIV on 1 Timothy v. 8” [20] )

| St. John Cassian the Roman [ca. 360-435], [21] in The Monastic Institutes devotes two entire books (Two and Three) in discussing these prayer offices. |

|

St. John Cassian the Roman |

Some idea of the importance of these prayer offices (as if Scripture was not enough) can be found in the writings of the Church Fathers:

When thou instructest the people, O bishop, command and exhort them to come constantly to church morning and evening every day, and by no means to forsake it on any account, but to assemble together continually; neither to diminish the Church by withdrawing themselves, and causing the body of Christ to be without its member.(Apostolic Constitutions, Book 2, LXI [22] )

But, if some, perhaps, are not in attendance because the nature or place of their work keeps them at too great a distance, they are strictly obliged to carry out wherever they are, with promptitude, all that is prescribed for common observance… None of these hours for prayer should be unobserved by those who have chosen a life devoted to the glory of God and His Christ. (St. Basil, Ascetical Works [23] )

The reason for this importance is tied up in the Orthodox understanding of ecclesiology and God’s economy, topics that are beyond the scope of this paper. In short, during corporate worship, we as members of Christ’s Body—the Church Militant—join together mystically with the rest of the Body, regardless of where we are physically located, as well as with that part of the Body that is in Heaven—the Church Triumphant—in offering up praise and prayers to God. But how does all this relate to the prayer rope? If you live near a church where you can attend these services, one might guess nothing, other than perhaps as an aid during the service to refocus your prayers after being distracted; our holy Fathers tell us otherwise.

|

The Elder Moses of Optina (1782-1862; commemorated 16 June, and 10 October along with the other Optina Fathers), for example, related an exhortation he had heard from St. Seraphim of Sarov (1754-1833; commemorated 02 January, and on the opening of his relics on 19 July): While you are standing in church, you must say the Jesus Prayer. Then you will also hear the church service distinctly. [24] |

St. Seraphim of Sarov |

However, if you are on travel, part of the Orthodox Diaspora, or a religious hermit, consider the following. As passed down to us by the Church Fathers, the basic framework for saying these Offices is contained in the Horologion. To fill out the framework, it is also generally necessary to have a Psalter, Octoechos, Menaion, Triodion, Pentecostarion, Evangelistarion, Apostolos, and liturgical calendar, as well as rubrics from a Typicon. There have been a few Saints who had a God-given ability to memorize this vast amount of material. Consider for example, St. Joseph, Hegumen of Volokolamsk [ca. 1439-1515]:

|

Contemporaries were astonished at his exceptional memory. Often, without having a single book in his cell, he would do the monastic rule, reciting from memory from the Psalter, the Gospel, the Epistles, and all that was required. [25] |

| St. Joseph, Hegumen of Volokolamsk |

However, such feats of memory are beyond most of us, and we must rely on the texts. But therein lies a quandary, for one can easily spend several thousand dollars building up such a library, to say nothing of carrying it with you! This, too, is clearly beyond what an average person can afford. What, then, is a person to do if one or more of these prayer services form part of their prayer rule as established in consultation with their spiritual director? The answer can be found in the church’s service books (e.g., the Russian Orthodox Service Psalter) where the Offices can be replaced by praying the Jesus Prayer a specified number of times. One scheme for this is as follows: [26]

- Vespers: 600 prayers

- Great Compline: 700 prayers

- Small Compline: 400 prayers

- Midnight Office (Nocturn): 600 prayers

- Matins: 1500 prayers

- The Hours without the Inter-Hours: 1000 prayers

- The Hours with the Inter-Hours: 1500 prayers

- A Canon or Akathist to the Most Holy Theotokos: 300 prayers

- Reciting the entire Psalter: 6000 prayers

- One kathisma of the Psalter: 300 prayers

- One stasis of the Psalter: 100 prayers

This solves one problem—how to pray the Offices when the prayer books aren’t available—but creates a new one: how to keep track of counting hundreds (or thousands) of prayers. One solution can be found in the Church fathers:

| Paul dwelt at Ferme [† ca. 339], a mountain of Scetis, and presided over five hundred ascetics. He did not labor with his hands, neither did he receive alms of any one, except such food as was necessary for his subsistence. He did nothing but pray, and daily offered up to God three hundred prayers. He placed three hundred pebbles in his bosom, for fear of omitting any of these prayers; and, at the conclusion of each, he took away one of the pebbles. When there were no pebbles remaining, he knew that he had gone through the whole course of his prescribed prayers. [27] |

|

St. Paul the Simple |

Needless to say, while this certainly works, there is a more practical solution: using the knots on a prayer rope for keeping count of the Jesus Prayers said when praying an Office without the service books.

|

The elders now living among us [at the end of the 19th century] in sketes or special kellia in places such as Valaam or Solovki serve the entire service according to this [method]. [28] (Theophan the Recluse [1815-1891]) |

Theophan the Recluse |

Other Prayer Rope Applications

There are two additional but similar uses of the prayer rope. First, monastics are often given cell rules that involve reciting a particular number of Jesus Prayers, often along with prostrations (such as the cell rule of five hundred [Jesus Prayers] of the Optina Monastery [29] ). Second, when saying an Office (or the Liturgy) with the service books, there are times when certain prayers are repeated enough times that a prayer rope can help keep count (e.g., saying “Lord have mercy” forty times).

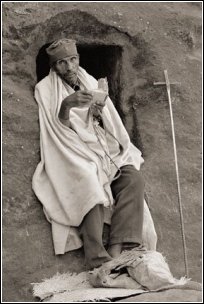

Prayer Rope Description

The earliest form of the prayer rope was, we can easily imagine, like that apparently used by St. Anthony the Great: a plated rope with knots made from palm fronds, [30] or perhaps from reeds gathered along the Nile River or Red Sea that he used in weaving baskets. [31] This type of prayer cord is still seen in portions of the Middle East, particularly in the desert monasteries. [32]

While the actual details are buried in history, as the use of the prayer rope spread, the preferred materials used in its making changed to leather and plaited wool yarn. We can surmise that such changes reflected both material availability and a desire for durability. In today’s world, the materials used by many have again changed—to synthetics—primarily for cost considerations.

It might be noted here that the most prevalent forms of traditional Orthodox prayer ropes are NOT an adaptation of the technique of Paul (of Ferme), i.e., a string of stones or beads—although, strictly speaking, there is nothing wrong with using a beaded prayer rope, and they can be found in use, e.g., among the Russian Fathers, where they are known as чётки, chotki. However, the traditional technique of using fronds, leather or wool is intended to produce a prayer rope that is quiet. Consider that practicing the Prayer of the Heart—hesychasm—is the practice of stillness such that one can hear their heart beat; the clicking of beads would only serve to distract and not to focus.

The Elder Moses of Optina holding a beaded prayer rope (чётки, chotki).

Probably the most common prayer rope found is a cord of 100 knots—which supports reciting the Offices by praying the Jesus Prayer a specified number of times as given above—that is ~2-feet long, formed into a loop (Greek: Κομποσκοίνι , komposkini; Russian: вервица , vervitsa, “small rope”); this is the type, e.g., found in use by the monks on Mt. Athos. The knots, ~¼” diameter, are generally closely “strung” together and are quite complex in form (knots of interlocked crosses as related earlier).

Typically there is a knotted cross where the prayer rope is joined together to form a loop. Frequently there is also a tassel at the end of the cross. In some prayer rope designs, additional strings with moveable beads—"martyria" (witnesses)—are attached to the main loop in order to keep track of the hundreds of times the prayer is recited. For those who recite a shorter rule (e.g., involving multiples of 10, 25, or 50), the prayer rope may be divided up in sections using larger than normal knots or, more typically, beads. In addition to prayer ropes of 100 knots, it is also possible to find prayer ropes of 10, 12, 33, 50, 150, 300, and 500 knots. The most important thing is to use a prayer rope of a suitable length and with appropriate dividers (or martyria) that matches one’s prayer rule (noting that if it is only being used to practice interior, Prayer of the Heart, the length or divisions thereof is immaterial).

In keeping with Orthodox tradition

to associate every day things with the Heavenly—and so direct our mind

there—the knotted cord prayer rope has its own symbology. The prayer rope

is traditionally made out of wool, symbolizing the flock of Christ, a reminder

that we are rational sheep of the Good Shepherd, Christ the Lord, and also a

reminder of the Lamb of God Who takes away the sins of the world (cf. John

1:29). The most prevalent (but not only) color of a prayer rope is black,

symbolizing mourning for one's sins. The tassel at the end of the cross is to

dry the tears shed due to heartfelt compunction for one's sins (or, if you have

no tears, to remind you to weep because you cannot weep); it can also be said

to represent the glory of the Heavenly Kingdom, which one can only enter

through the Cross. The beads (if they are colored)—and possibly a portion

of the tassel—are traditionally red, symbolizing the blood of Christ and

the blood of the martyrs. And of course the cross itself speaks to us of the

sacrifice and victory of life over death, of humility over pride, of

self-sacrifice over selfishness, of light over darkness. Finally, the manner of

tying the knots may produce either seven or nine crosses in each separate knot,

symbolizing the seven heavens or the nine ranks of angels.

In keeping with Orthodox tradition

to associate every day things with the Heavenly—and so direct our mind

there—the knotted cord prayer rope has its own symbology. The prayer rope

is traditionally made out of wool, symbolizing the flock of Christ, a reminder

that we are rational sheep of the Good Shepherd, Christ the Lord, and also a

reminder of the Lamb of God Who takes away the sins of the world (cf. John

1:29). The most prevalent (but not only) color of a prayer rope is black,

symbolizing mourning for one's sins. The tassel at the end of the cross is to

dry the tears shed due to heartfelt compunction for one's sins (or, if you have

no tears, to remind you to weep because you cannot weep); it can also be said

to represent the glory of the Heavenly Kingdom, which one can only enter

through the Cross. The beads (if they are colored)—and possibly a portion

of the tassel—are traditionally red, symbolizing the blood of Christ and

the blood of the martyrs. And of course the cross itself speaks to us of the

sacrifice and victory of life over death, of humility over pride, of

self-sacrifice over selfishness, of light over darkness. Finally, the manner of

tying the knots may produce either seven or nine crosses in each separate knot,

symbolizing the seven heavens or the nine ranks of angels.

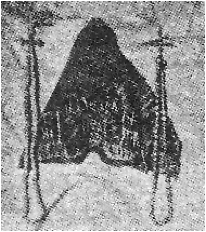

There is also a leather form of the prayer rope that is still

in use—albeit rarely—which comes down to us through traditions of

the Russian Orthodox. This leather prayer rope is made of strips ~½”

wide that are cut, intertwined, and sewn (or glued) together to form a flat

rope ~2-feet long, whose ends are also sewn together. The strips themselves are

folded into a series of small loops ~

![]() ” in diameter, each often containing a short length of

small-diameter dowel to help it keep its shape; one small loop forms one prayer

counter. The main loop of a leather prayer rope normally contains 100 such

small loops. This sequence of 100 is divided into four, shorter groups of

counters: 12, 38, 33, and 17. These sections are separated by three divider

loops of ~¼” diameter (i.e., larger than the small counting loops). Each

end of the main loop of the prayer rope also includes three divider-sized loops

(for a total of nine) that are separated from the counters by a ~½”-long

space. To complete the prayer rope, four triangular leaves are attached to the

point where the ends are joined; these are sewn together two and two, the upper

pair overlapping the lower.

” in diameter, each often containing a short length of

small-diameter dowel to help it keep its shape; one small loop forms one prayer

counter. The main loop of a leather prayer rope normally contains 100 such

small loops. This sequence of 100 is divided into four, shorter groups of

counters: 12, 38, 33, and 17. These sections are separated by three divider

loops of ~¼” diameter (i.e., larger than the small counting loops). Each

end of the main loop of the prayer rope also includes three divider-sized loops

(for a total of nine) that are separated from the counters by a ~½”-long

space. To complete the prayer rope, four triangular leaves are attached to the

point where the ends are joined; these are sewn together two and two, the upper

pair overlapping the lower.

Lestovka.

Like the knotted cord prayer rope, the leather version has its own symbology. At the macro-scale, this prayer rope is intended to resemble a ladder, which is its prevalent name in Church Slavonic: лѣстовка (lestovka). Thus the form of the prayer rope itself reminds its user that prayer is a spiritual ascent into heaven. Association may also be made with the practice of hesychasm as found in the Ladder of Divine Ascent written by St. John Climacus. The four different sized groups of counters are also given meaning as follows: 12 for the number of Apostles; 38 plus the dividers on each end total 40, which is the number of weeks for human gestation and thus reminds us of the pregnancy of the Theotokos; 33 for the years of Christ's life on earth; and 17 for the number of prophets. The nine dividers represent the nine ranks of angels. The four triangular leaves represent the four Gospels.

The lestovka form of the prayer rope is also suited for counting litany responses and prostrations. For example, the groupings of 12 and 40 (38 plus 2 dividers) can be used for counting “Lord have mercy” responses that are found in many of the Offices. Other combinations, such as 30 and 50, are also possible. For such liturgical purposes it is clearly more practical than the more familiar variety of knotted cord prayer rope.

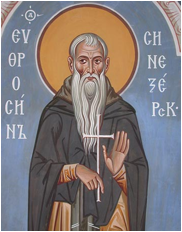

Tradition tells us that the lestovka came to Russia from Jerusalem. We can speculate that its arrival there coincided with the work of St. Cyprian, metropolitan of Moscow and Kiev, when, at the end of 14th century, he undertook actions to replace the Studite liturgical practices originally introduced in the 11th century through the efforts of St. Theodosius with the Jerusalem Typicon (or Typicon of St. Sabbas). However, little can be said of its actual introduction or prevalence in use. While “Old Believers” would have you believe that the lestovka was the form of prayer rope in use in Russia prior to the reforms of Patriarch Nikon in 1652, it is easy to show that this was not the case (just as they are wrong about early Russian traditions concerning how to make the Sign of the Cross). Consider, for example, Saint Euphrosynus of Blue Jay Lake ( Cв. Евфросин Синеезерский ), a schemamonk and abbot who was martyred by the Latins on March 20, 1612. When his relics were uncovered in 1655, they were found to be incorrupt; also preserved with him were the Schema-epitrachelion, -cowl, and two prayer ropes that the Saint was wearing when he was martyred and buried (note that, although the photograph shown below is of poor quality, [33] the prayer ropes appear to be чётки (chotki), but in any case, they are clearly not lestovka).

|

|

| St. Euphrosynus of Blue Jay Lake and his monastic cowl and two prayer ropes. | |

Using the Prayer Rope[34]

When praying, the prayer rope is normally held in the left hand, leaving the right hand free to make the Sign of the Cross. When not in use, the prayer rope is traditionally wrapped around the left wrist so that it continues to remind one to pray without ceasing. If this is impractical, it may be placed in the (left) pocket, but should not be hung around the neck or suspended from the belt. The reason for this is humility: one should not be ostentatious or conspicuous in displaying the prayer rope for others to see.

Epilogue

The hesychast’s practice of repeatedly praying the Jesus Prayer is considered to be second only to the Divine Liturgy in terms of importance to the spiritual well being and development of an Orthodox Christian. That inevitably means that the devil will be hard at work trying to cause distractions while we are at prayer, and, insofar as he becomes successful in that regard, he will attempt to lure us to neglect and eventually supplant our prayer with other activities. If we let our prayer life wane, it won’t be long before spiritual things in their entirety begin to slip away. And if that happens, how will we prevent the devil from completely dominating our life and avoid alienating ourselves from God? The watchword: persevere in prayer.

The Elder Joseph the Hesychast with his “sword” (prayer rope; photograph provenance unknown).

There is also one other point I would like to stress: saying the Jesus Prayer is important for all Orthodox Christians. The discussion to this point has invoked examples and sayings from many monastic fathers that may lead one to erroneously believe that it is really not meant for lay people. This would be wrong. Consider the following entry from the Prologue: [35]

Does the Lord's commandment about unceasing prayer (Lk.18:1) apply only to monks, or to all Christians? If it applied only to monks, the Apostle would not have written to the Christians in Salonica: 'Pray without ceasing' (I Thess. 5:17). The Apostle, then, reiterates the Lord's command word for word, and gives it to all Christians without distinction of monk or layman. St Gregory Palamas lived for some time as a young man in a monastery in Beroea. There lived in those parts a well-known ascetic, the elder Job, who was venerated by all. It happened at one time that St Gregory, in the elder's presence, quoted the Apostle's words, asserting that unceasing prayer was a necessity for all Christians, not only for monks. The elder Job replied to these words, saying that the Jesus prayer is a necessity only for monks, and not for all Christians. Gregory, being a young man, ceded the argument, not wishing to quarrel, and withdrew in silence. When Job had returned to his cell and was standing in prayer, an angel of God appeared to him in great heavenly glory, and said to him: 'Old man, don't doubt the truth of Gregory's words; he spoke truly. So, hold your peace and advise others to do the same.' Thus, then, both the Apostle and the angel underlined the commandment that all Christians must pray to God without ceasing. If not unceasingly in church, then unceasingly in every place and at every time, in the depths of your heart. If God does not for a moment tire of giving us good things, how can we tire of thanking Him for these good things? If He is constantly thinking of us, why do we not think constantly of Him?

Appendix: The St. Pachomius Prayer Rule

As compiled and emended from various sources. [36]

Through the prayers of our holy Fathers, O Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy upon us.

Amen.

Glory to Thee, our God, Glory to Thee.

O Heavenly King, the Comforter, the Spirit of Truth, Who art in all places and fillest all things, Who art the treasury of good-things and the giver of life; come and make Thine abode in us, and cleanse us from all impurity, and save our souls, O Good One.

Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy upon us.

Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy upon us.

Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy upon us.

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit:

Both now, and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

All-Holy Trinity, have mercy upon us. O Lord, purify us from our sins. O Master, forgive us our transgressions. O Holy One, look down upon us, and heal our infirmities for Thy name’s sake.

Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy.

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit:

Both now, and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

Our Father, Who art in the heavens, hallowed be Thy name; Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven: give us this day our daily bread: and forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors, and let us not be brought into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.

Through the prayers of our holy Fathers, O Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy upon us.

Amen.

Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy.

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit:

Both now, and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

О come, let us worship, and bow down to our King and God.

О come, let us worship, and bow down to Christ, our King and God.

О come, let us worship, and bow down to Christ Himself, our King and God.

Psalm L (50)

Have mercy on me, O God, according to Thy great mercy; and according to the multitude of Thy compassions, blot out my lawlessness. Wash me thoroughly from my lawlessness, and cleanse me from my sin. For I know my lawlessness, and my sin is before me continually. Against Thee alone did I sin and commit evil before Thee, so that Thou shouldest be justified in Thy words and shouldest prevail when Thou art judged. For, behold, I was conceived in iniquities, and in sins did my mother conceive me! For, behold, Thou didst love truth! The secret and hidden things, of Thy wisdom didst Thou make manifest to me. Thou shalt sprinkle me with hyssop, and I shall be cleansed; Thou shalt wash me, and I shall be made whiter than snow. Thou shalt make me to hear joy and gladness; the bones having been humbled, they shall rejoice exceedingly. Turn away Thy face from my sins, and blot out all my lawless deeds. Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew an upright spirit in mine inmost parts. Do not ever cast me away from Thy presence; and Thy Spirit, the Holy One, do not ever take away from me. Restore to me the great joy of Thy salvation, and with Thy governing Spirit support me. I shall teach lawless ones Thy ways, and impious ones shall return to Thee. O God, the God of my salvation, deliver me from the guilt of shedding blood; my tongue shall rejoice exceedingly in Thy righteousness. Thou, O Lord, shalt open my lips, and my mouth shall proclaim Thy praise. For if Thou didst wish sacrifice, I would have given it; Thou shalt not find pleasure in whole burnt-offerings. A sacrifice to God is a spirit having been made contrite; a heart having been made contrite and humble God will not treat with contempt. Do good, O Lord, in Thy good pleasure to Sion, and let the walls of Jerusalem be built. Then shalt Thou find pleasure in a sacrifice of righteousness, in oblation and whole burnt-offerings. Then shall they offer young bulls upon Thine altar.

The Symbol of Faith

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Only-begotten, begotten of the Father before all ages; Light from Light, vегу God of vегу God, begotten, not made, Being of one Essence with the Father, bу whom аll things were made; Who for us men, and for our salvation, сomе down from the heavens, and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Маrу, and was made Маn; And was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered and was buried; And rose again the third day according to the Scriptures; And ascended into the heavens, and sitteth at the right of the Father; And shall come again with glory to judge both the living and the dead, of whose kingdom there shall be nо end. And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of life, who proceedeth from the Father, who with the Father and the Son is together worshipped and glorified, who spake bу the Prophets. In оnе, holy, catholic, and apostolic Сhurch. I confess оnе Baptism for the remission of sins. I look for the Rеsurrection of the dead, And the life in the ages to come. Amen.

The Jesus Prayer

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy, on me. (100 Times)

The Dismissal

The Theotokion of the Anaphora

It is truly meet to call thee blessed, the Theotokos; the ever-blessed, and most pure, and Mother of our God. More-honourable than the Cherubim, and beyond compare more glorious than the Seraphim; who didst bear without corruption God the Word: thee, verily the Theotokos, we magnify.

Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit:

Both now, and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy.

O Lord, Bless.

O Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, for the sake of the intercessions of Thy all-pure Mother, of our reverend and God-bearing fathers, and of all the Saints, have mercy upon us and save us, as the only Good One and Lover of man. Amen.